The Caribbean case for reparative justice

By David A. Granger

Address by His Excellency Brigadier David Granger, President of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana to the International Youth Reparations Relay and Rally, Independence Park, Georgetown.

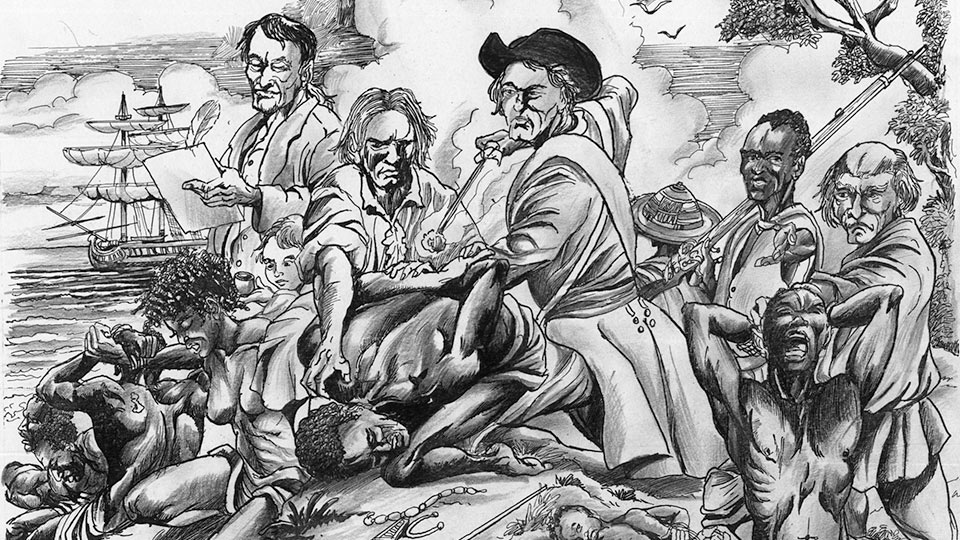

The trans-Atlantic trade in captive Africans

The trans-Atlantic trade in captive Africans “was the largest forced transportation of human beings from one part of the globe to another in the world’s history and, certainly, one of the greatest unnatural disasters of all time.”

The trans-Atlantic trade involved the systematic capture, transportation, sale and enslavement of human beings. The trade started in 1441 (not 1492, as some persons mistakenly believe), persisted for four hundred years and involved four continents.

The enslavement of Africans was a crime against humanity. The World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance held in Durban, South Africa from August 31-September 8, 2001 acknowledged “… that slavery and the slave trade are a crime against humanity and should always have been so …”

There was a crime. There has been no justice. The enslavement of Africans, the decimation of the indigenous population and the oppression of indentured immigrants all constituted crimes and, therefore, a call for ‘reparative justice.’

‘Reparative justice’ concerns the legal obligations of states. “States have a legal duty to acknowledge and address widespread or systematic human rights violations, in cases where the state caused the violations or did not seriously try to prevent them…Reparations publicly affirm that victims are rights-holders entitled to redress.”

The descendants of the colonized peoples of the Caribbean, therefore, are correct in their call for ‘reparative justice’ to right these wrongs. The victims of these crimes against humanity have been deprived of an apology. They have been deprived of ‘reparative justice’ for the abominable crimes that resulted in the loss of millions of lives, the expropriation of the wealth and the legacy of underdevelopment.

Guyana, our homeland, was a victim of almost three hundred and fifty years of European colonization. Guyana’s experiences mirrored, more or less, the experiences of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) member States. The exploitation of the people’s labour, the expropriation of wealth, the enrichment of metropolitan centres and the distortions of colonial rule have heightened calls throughout the Caribbean for ‘reparative justice’.

CARICOM and ‘reparative justice’

The people of the Caribbean look to their leaders to bring about redress for the crimes inflicted on their ancestors and the damage done to their societies. Caribbean political leadership has been responsive to these pleas.

The Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, at their Thirty-fourth Regular Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community held in Trinidad and Tobago on 3-6 July 2013, agreed unanimously to establish national reparations committees and to appoint a high-level committee to oversee the work of a CARICOM Reparations Commission.

The Heads of Government, at the conclusion of the Twenty-fifth Inter-sessional Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) held on 12th March 2014 in St Vincent, accepted , as the basis for further action, the Draft Regional Strategic and Operational Plan for a Caribbean Reparatory Justice Programme (CRJP).

This Draft Plan – known as the Action Plan – was prepared by the Regional Reparations Committee which comprises the Chairpersons of the national reparations committees. The Action Plan proposed ten areas for reparations:

- An apology: A full formal apology from the governments of European states;

- A development plan: A plan for the development of indigenous communities;

- A cultural plan: A Plan for the establishment of cultural institutions;

- A health plan: A Plan for arresting the health pandemic in the Caribbean caused by chronic diseases;

- An education plan: A plan for the eradication of illiteracy;

- A technology plan: A technology transfer plan to narrow the technological gap between Europe and the Caribbean;

- A resettlement programme: A resettlement and reintegration programme for those wishing to return to their homelands;

- An African knowledge programme: The development of an African knowledge programme to bridge the cultural and social alienation that was created when Africans were forcibly removed from their homeland;

- A psychological rehabilitation programme: A programme of psychological rehabilitation to heal and repair the psychological trauma of slavery;

- A debt cancellation Plan: A debt cancellation plan to overcome the poverty and institutional weaknesses.

Crimes against humanity

The case for ‘reparative justice’ can be established in respect to three principal claims:

- first, that the acts of enslavement and genocide clearly, are crimes against humanity; they require an acknowledgment of wrongdoing and recompense through reparations;

- second, that Europe’s enrichment through the expropriation and transfer of the wealth of the Caribbean was an unjust enrichment; the Caribbean should enjoy reparations for the exploitation and deprivations inflicted;

- third, that enslavement and genocide have left a legacy of underdevelopment, which can only be overturned through corrective justice.

The first basis for claims for ‘reparative justice’ rests on the fact that crimes against humanity are punishable under international law and do not enjoy protection by any statute of limitations. Article 6 of the Charter of the International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg of 1945, lists “enslavement’ as a crime against humanity. Genocide is also prosecutable offence under the jurisdiction of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court of 1998.

States, organizations and institutions which are complicit in crimes against humanity do not enjoy immunity from the passage of time. The Convention on the non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on November 26, 1968 provides that no statutory barrier shall apply to “ crimes against humanity whether committed in time or war on in time of peace…”

Enslavement and genocide, therefore, are prosecutable offences and for which there are no statutes of limitations under international law.

Expropriation of wealth: The second basis for claims for ‘reparative justice’ rests on the evidence that huge wealth was generated during the commission of these crimes against humanity by European colonizers and the expropriation and transfer of that wealth to European states.

Colonization allowed for the unjust enrichment of Europe. The vast wealth extracted through forced labour in the colonies of the Caribbean enriched the coffers of generations of European families and impoverished those whose servitude generated those fortunes. This wealth was acquired through the forceful subjugation of entire peoples.

Legacy of colonialism: The third basis for claims for ‘reparative justice’ is that the Caribbean, even after being granted Independence, is yet to shake off the legacy of colonialism. Colonization has underdeveloped the Caribbean. This Region, as a consequence of European conflict and conquest, became the most Balkanized region in the world. The Caribbean today is fragmented. Its economic structures still bear the stamp of the ‘plantation economy’ with a high concentration on primary production for export to western markets, including Europe.

The CARICOM Reparations Commission observed that the descendants of the victims of enslavement have been left in:

…a state of social, psychological, economic and cultural deprivation and disenfranchisement that has ensured their suffering and debilitation today, and from which only reparatory action can alleviate their suffering.

European states have a clear understanding of the concept of ‘reparative justice’.

- Britain swiftly paid compensation to the plantation owners for the loss of their “property” on the emancipation of enslaved Africans. No similar payment was made to those who had been enslaved and who were forced to provide ‘free’ labour during the apprenticeship period – 1834-1838. They ended up bearing more than half of the millions of pounds actually paid as compensation to the planters.

- Britain also paid compensation to victims of torture during the Mau-Mau uprising in Kenya.

- Germany was forced to pay reparations to the Allies after World War I and World War II. Germany also agreed to pay reparations to Israel under the Luxembourg Agreement of 1952.

- Japan paid compensation to a number of countries for its role in World War II.

The Caribbean is not begging for hand-outs or aid. The Caribbean is not soliciting sympathy. The Caribbean is not seeking favours. The Caribbean is demanding ‘reparative justice’ for the greatest crime against humanity in the history of the world – the trans-Atlantic trade in captive Africans.

The Caribbean’s case for ‘reparative justice’ is righteous. The struggle for ‘reparative justice’ will be long but every just cause is worth fighting for. May God consecrate our efforts! I thank you.