History shows slavery helped build many U.S. colleges and universities

STORY: Stephen Smith | Kate Ellis

As more schools begin to confront their participation in slavery, they also consider how to make amends.

Dozens of American colleges and universities are investigating their historic ties to the slave trade and debating how to atone.

Profits from slavery and related industries helped fund some of the most prestigious schools in the Northeast, including Harvard, Columbia, Princeton and Yale. And in many southern states — including the University of Virginia — enslaved people built college campuses and served faculty and students.

Today a growing movement to confront this legacy is being spurred by student protests and campus leaders reacting to high-profile racial conflict that has recently beset the nation. The result has been historical investigations, university commissions, conferences, memorials, and, at Georgetown, a handful of the descendants of enslaved people arriving as first-year students at the institution that owned their ancestors.

“The story of the American college is largely the story of the rise of the slave economy in the Atlantic world,” says Craig Steven Wilder, a historian at MIT and author of “Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities.”

Early benefactors who gave money to Brown and Harvard, for instance, made their fortunes running slave ships to Africa and milling cotton from plantations in the American South. Georgetown could afford to offer free tuition to its earliest students by virtue of the unpaid labor of Jesuit-owned slaves on plantations in Maryland. At the University of Virginia — founded and designed by Thomas Jefferson — slaves cooked and cleaned for the sons of the Southern gentry.

“Yale inherited a small slave plantation in Rhode Island that it used to fund its first graduate programs and its first scholarships,” Wilder says. “It aggressively sought out opportunities to benefit from the slave economies of New England and the broader Atlantic world.”

To date, there is no single accounting of how much money flowed from the slave economy into coffers of American higher education. But Wilder says most American colleges founded before the Civil War relied on money derived from slavery. He suspects that many institutions are reluctant to examine this past. “There’s not a lot of upside for them. You know these aren’t great fundraising stories,” Wilder says.

Some people say that institutions must do more than make apologies and rename buildings. They insist that scholarships and other forms of monetary reparations are due. And others argue that whatever colleges and universities are doing to acknowledge their slave-holding past — a campus memorial to slaves, for example — is motivated by public relations and does nothing to ameliorate the legacy of slavery and systemic inequality.

Brown University was the first to confront its ties to slavery in a major way. In 2003, Brown president Ruth Simmons appointed a commission to investigate. “What better way to teach our students about ethical conduct than to show ourselves to be open to the truth, and to tell the full story?” she says.

At Harvard, a professor and his students investigated the university’s past and found slavery hiding in plain sight. The University of Virginia in Charlottesville is naming buildings for enslaved people who worked there, and teaching high school students about how modern racial inequities are rooted in the slaveholding past. Georgetown is creating an institute to study slavery and has apologized to the families of enslaved people it sold.

Simmons says the recent rise of racial conflicts in the United States is a reprise of past wrongs that went unresolved. She says colleges can promote reconciliation by thoroughly examining their pasts. “We don’t have to fight about it. We don’t have to be angry about it,” Simmons says. “But we do have to come to terms with it.”

What follows are stories of three universities investigating their ties to slavery and grappling with how to make amends for this history.

At Harvard, markers of slavery

The two gray slate headstones stand just yards apart.

They look like many of the thousand or so other markers in the Old Burying Ground in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Each has a name and a date chiseled into the surface and a skull-and-wings emblem — a symbol dating to medieval times — carved at the top.

The markers are modest, smaller than others, yet profoundly unusual, the only ones in the cemetery. They sit atop the graves of African American slaves.

One reads: “Here lyes the body of Cicely, Negro, late servant to the Reverend Minister William Brattle; she died April 8, 1714. Being 15 years old.”

The other: “Jane a Negro servant to Andrew Bordman Esquire Died 1740/1 Aged 22 years & three months.”

The stones are significant for another reason: The Brattle and Bordman families had close ties to Harvard College, which has a long and deep connection to slavery.

Harvard was the first institution of higher learning in America, founded in 1636. Slavery and the slave economy thread through the first 150 years of its history. Slaves made beds and meals for Harvard presidents. The sons of wealthy Southern plantation owners became prominent men on campus. And many of the school’s major donors in its first centuries made their fortunes in industries either based on, or connected to, slavery.

The evidence of Harvard’s historic links to slavery are there, if you know where to look for them. Jane and Cicely make for unusual clues, according to a Cambridge historian. Few enslaved people were buried with expensive slate headstones. But Jane and Cicely were honored in death after loyally serving prominent Harvard men.

Harvard’s ties to slavery were never a secret. Today, however, they’re hardly common knowledge on campus and they’re generally not reflected in official histories of the university.

That started to change in 2007, when Sven Beckert, a professor of American history, taught a seminar with four Harvard undergraduates. Their mission: dig into the school’s archival records to see what traces of slavery they could find. Beckert had been inspired by Simmons’ commitment at Brown.

They soon discovered that prominent Harvard figures — including the Puritan Minister Cotton Mather and the Declaration of Independence signatory John Hancock — were slave owners. “In some ways we were surprised by what we found,” Beckert says. “Of course, it was ridiculous that we were surprised, because clearly the economy of New England was deeply engaged with the slave economy.”

A long legacy of slavery

In fact, Massachusetts was the first colony to legalize slavery, in 1641.

Sugar plantations in the Caribbean devoted most of their land to growing cane. They imported grain, meat, codfish and other supplies from New England. Ship owners in New England hauled back barrels of molasses to make rum. Then they shipped the rum to Africa to pay for slaves. New England merchants used part of the profits from this triangular trade to finance Harvard and other schools.

Over time, cotton from slave plantations in the Caribbean and the American South entered the mix. Cotton fed the great textile mills owned by the Lowell family of Boston, which had extensive ties to Harvard, including a Harvard president and a prominent professor. Banks in Boston and New York supplied loans to southern plantation owners to buy slaves and seed; northern insurance companies underwrote slave voyages to Africa and the lives of enslaved people.

“Enslavement and the slave economy was the road for upward mobility for a lot of white Bostonians in the colonial era, and then the antebellum era. And part of becoming respectable is donating to a place like Harvard,” says Kathrine Stevens, assistant professor of history at Oglethorp University in Atlanta. Stevens was a Harvard graduate student when she helped Beckert teach his seminar.

Scientific racism is another of Harvard’s legacies. In the 19th and 20th centuries, some Harvard professors proposed scientific theories they said proved the inherent inferiority of black people. Chief among them was Louis Agassiz, the geologist and zoologist often described as one of the “founding fathers” of American science.

Agassiz promoted the idea of polygenism — that the different races descended from different species. Other Harvard scientists propagating scientific theories of white superiority were Nathanial Shaler, dean of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard, and anthropology professor Earnest Hooton.

“The work they did contributed greatly to legitimizing slavery in the 19th century and to the discrimination that followed,” says Zoe Weinberg, a student at Yale Law School who took Beckert’s seminar as an undergraduate at Harvard. “Harvard really acted as a pioneer and champion of the field of race science. That was a history I was totally unaware of as a student.”

Anti-slavery activists on the Harvard campus were pariahs for much of the antebellum period. Harvard professors who spoke openly against slavery invited fierce criticism from Boston newspapers and risked losing their jobs. In 1838, the Philanthropic Society of Harvard’s Divinity School staged a debate on abolition. Harvard President Josiah Quincy discouraged, but did not ban, the event.

When Beckert’s history students finished their research, they presented it to Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust, a historian of the Civil War and the American South. Faust found money for Beckert and his students to write a short book, titled “Harvard and Slavery.” This past March, Faust and Harvard held a major conference on universities and slavery, drawing people from around the world.

“Harvard was directly complicit in slavery from the college’s earliest days,” Faust told the overflow crowd. “This history and its legacy have shaped our institution in ways we have yet to fully understand.”

Under pressure from students, the Harvard Law School in 2016 retired its shield — essentially its logo — because it was based on the family crest of an 18th century slave-holding family of Isaac Royall Jr., who endowed the first law professorship at Harvard in 1815, described as the most distinguished chair in American legal education. Royall’s father was a Caribbean plantation owner who built the family fortune trading in sugar, rum and slaves.

At the Harvard slavery conference, keynote speaker Ta-Nehisi Coates, who has written powerfully about the African American experience, argued that the university — indeed all higher education institutions with historic links to slavery — needs to do more than publish histories, change logos and similar acts of recognition. “I think every one of these universities needs to make reparations,” said Coates, who wrote a prominent magazine article in 2014 arguing the general case. “I don’t know how you get around that. I don’t know how you conduct research that shows that your very existence is rooted in a great crime and shrug, say you’re sorry and just walk away.”

The sin of slavery at Georgetown

By the time the Jesuit priests of Maryland founded Georgetown College in 1789, they were among the biggest slave owners in the colony.

With several tobacco plantations scattered across Maryland, the Catholic order owned at least 200 slaves. It used the income from their labor to create Georgetown, part of an educational mission to spread and maintain Catholicism in the U.S.

“The idea was that the Jesuit plantations manned by enslaved people would essentially subsidize the Jesuit educational mission,” says Adam Rothman, a historian at Georgetown University, explaining the purpose and economics of free tuition.

Georgetown also directly employed slave labor, says Rothman, citing the school’s early ledgers showing rented or hired enslaved people.

By the 1810s, the Jesuits’ tobacco plantations failed, and Georgetown was in debt. For some 20 years, the priests debated whether to free their slaves, keep them as part of their religious stewardship or sell them.

The Maryland Jesuits decided to sell 272 men, women and children — virtually their entire slave community — to two planters in Louisiana. They were paid $115,000, roughly $3 million in current dollars. The money helped pay off Georgetown’s debts. In 1838, the enslaved people were divided and sent by ship to Louisiana.

Nearly two centuries later, Georgetown President Jack DeGioia formed the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation to investigate that history and recommend ways to atone.

As college students increasingly became part of nationwide protests against a spate of police killings of unarmed black men, they also gave voice to claims of entrenched racism on their campuses.

By 2015, DeGioia felt it was time for Georgetown to examine itself. “We realized that this was a moment where we needed to have a conversation at Georgetown on our history, and how our history connects to this particular moment in our nation,” he says.

That conversation soon took on a new meaning after a surprising discovery later that fall. In November 2015, Georgetown students demanded that two buildings on campus named for Jesuit priests who orchestrated the slave sale be renamed. Richard Cellini, a Georgetown graduate, read about the student protests and wondered what had happened to the slaves when they were sold to Louisiana.

Cellini, who is white, says he had never thought much about race issues. But he wrote a note to a member of the working group asking what happened to the slaves who were sold. The person replied that they had all died when they got to Louisiana, speculation never endorsed by the university. To Cellini, this just didn’t make sense. “It just struck me as statistically impossible,” he says. “I mean, even the Titanic had survivors.”

Cellini ran a Google search and found Patricia Bayonne-Johnson, who in 2004 discovered that she was the descendant of slaves sold by the Jesuit leaders of Georgetown. Judy Riffel, a genealogist in Baton Rouge who specializes in African American ancestry, had helped her figure this out. Cellini contacted the women and says that within hours he’d uncovered the truth. “Hundreds of the Georgetown slaves survived for decades after the Civil War,” Cellini says. He reckoned that thousands of their descendants were alive today.

Cellini hired Riffel and a team of genealogists to track down the 272 slaves and their descendants. He started a nonprofit, the Georgetown Memory Project (GMP), to fund the work. He says it costs roughly $235 to identify each slave or a descendant.

The GMP has identified and documented the lives of 212 of the original members of the “GU272,” the nickname Georgetown students gave the group of slaves as they tweeted their protests — #GU272. The GMP has traced and verified 5,095 direct descendants, living and deceased.

The vast majority of the GU272 descendants alive today reside in southern Louisiana. Many live just a few miles from the cotton and sugar cane plantations where their ancestors were sent in 1838.

A surprising gift: family history

One of these descendants is Jessica Tilson, a 35-year-old student at Southern University who’s raising two girls.

Tilson grew up in Maringouin, Louisiana, a small town west of Baton Rouge. Two bayous cut through Maringouin, and flat farmland stretches in all directions. She brings us to the Immaculate Heart of Mary cemetery, where at least 10 of the Maryland slaves are buried, all of them Tilson’s ancestors.

Once Tilson discovered she was a descendant of the GU272, she became an expert on who was buried in the cemetery, using an old burial guide from her church. “I walked this whole cemetery with the map,” she says. Some bodies are buried on top of others, so discovering exactly who was buried where was tricky.

Tilson often comes to the cemetery to clean the old grave markers. She gently scrubs them with a mixture of flour and water. “I do it mostly in the summertime,” she says. “It’s hot, but it helps the concrete dry faster.”

The Immaculate Heart of Mary cemetery is segregated. A road divides the white and black sections. Tilson says all the people on the black side are cousins. In fact, hundreds of black people still living in Maringouin are cousins.

The enslaved families who came down together from Maryland intermarried. When Tilson was growing up, she and her friends were told they shouldn’t date each other because they were related. But no one knew exactly how. “Come to find out,” Tilson says, “we’re related to each other about five different ways.”

Standing in the cemetery, Tilson sounds upbeat as she catalogs the ancestors who were sold. Discovering her family’s origins has felt like a gift, from Georgetown. “If it wasn’t for them,” she says, “I would never have known my family are from Maryland. I can’t be mad at them because [they] gave me something that a lot of African-Americans don’t have. [They] gave me my history back.”

African Americans trying to find their ancestors often can’t get past 1870.

That was the first year the federal census began routinely identifying black people by last name. Many slave-holding records only list black people by first name, if at all. Cellini explains that was not the case with the Jesuit plantation owners in Maryland. They kept meticulous records of their human property, including: first and last names, date of birth, parents’ names, date of baptism, first communion, confirmation, weddings and funerals.

“I think the Roman Catholic Church is the only organization in the world that records its wrongdoing in triplicate and then preserves it for decades,” Cellini says.

Georgetown University holds a lot of these records. They include the original Articles of Agreement for the 1838 sale, which lists all 272 people to be sold by the Jesuits. They also include the ship manifest of the Katherine Jackson, one of three ships that carried the slaves to Louisiana. These documents have been crucial in identifying the descendants of the Georgetown slaves and mapping the ways they’re related to each other.

Karran Harper-Royal is the executive director of the GU272 Descendants Association, which formed earlier this year. She lives in New Orleans and discovered she and her family are descendants of the Maryland slaves after a front-page story about the Jesuit slave sale ran in the New York Times. The Descendants Association exists, Harper-Royal says, to reconnect families torn apart by slavery.

Harper-Royal says that when descendants first learn how the Maryland Jesuits sold their ancestors, they’re hit with a mixture of emotions. “Initially,” she says, “you kind of hate everybody that enslaved your ancestors.” But then people figure out how to channel that anger.

Harper-Royal is on a mission to connect GU272 descendants with their history, and with each other. In January, she led the association’s first genealogy workshop for potential descendants. It was held at a public library in New Orleans and had the feel of a family reunion. About 25 people showed up, bringing trays of chicken wings, deviled eggs, and fruit.

Harper-Royal opened the gathering with an overview of the slave sale and reminded her audience, “These people are our relatives.” She helped attendees interpret results they got from home DNA tests. Soon enough, cousins were meeting cousins for the first time.

Harper-Royal has also been working with Georgetown to map a way forward. DeGioia, Georgetown’s president, formed the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation in the fall of 2015, before the student protests, and before Richard Cellini had tracked down any descendants. DeGioia says he would never have presumed the descendants wanted to engage with Georgetown. “But once it emerged that they did,” he says, “my judgment was it was important to make this personal.”

In June 2016, DeGioia traveled to Louisiana to meet with descendants. A few months later, he announced the Georgetown working group’s recommendations. They included building a campus research center to study slavery and its legacy, and collaborating with the descendant community to create a public memorial to the slaves the Jesuits sold.

DeGioia also announced that Georgetown was granting legacy status to all the descendants of the GU272, giving descendants the same preference in admissions that the children of alumni get.

“We provide care and respect for the members of the Georgetown community: faculty, staff, alumni, those with an enduring relationship with Georgetown. We will provide the same care and respect to the descendants,” DiGioia said.

DeGioia promises that these are just first steps. He has vowed to continue working with the descendant community, but some descendants are skeptical of Georgetown’s ability to be a model for change.

Sandra Green Thomas is the president of the GU272 Descendants Association. She says the university’s decision to offer legacy status to the descendants is insufficient and that descendants should have their own status. “Our contribution and sacrifice is unique and singular,” she says. “People that have donated money to that school have done so by choice. Enslavement was not by choice.”

But Thomas plans to continue to work with Georgetown. Two of her children are starting school there this fall.

In April, Georgetown held a ceremony to formally apologize to the descendants of the 272 men, women and children who were sold in 1838.

People sang, prayed and several of the descendants spoke, including Sandra Green Thomas. She said the pain of slavery may have lessened over the generations, but it is not gone. “Our disappointments, and the fortitude needed for daily survival, are both dwarfed by the experiences and the strength of those stalwart people who were ripped from their home place and sent to Louisiana,” Thomas said. “Their pain was unparalleled. Their pain is still here. It burns in the soul of every person of African descent in the United States.”

DeGioia spoke on behalf of Georgetown: “To the members of the descendant community, to the women and men that we have been privileged to meet, to all of you we have not yet met, and to those that we are unable to meet, we offer this apology for the sins against your ancestors, humbly and without expectation.”

More than 100 descendants attended the ceremony, including Tilson and Harper-Royal. They each spoke in another ceremony to rename the two buildings students had demanded be changed. One building is named after Isaac Hawkins, the first person listed in Articles of Agreement for the Jesuits’ slave sale. The other building is named after the pioneering black educator, Anne Marie Becraft.

Capping the day was a memorial tree-planting ceremony, where the names of all 272 people who were sold were read aloud. A white oak was chosen, since it grows in both Maryland and Louisiana. When Tilson met DeGioia during his visit to Louisiana, she gave him jars of soil from the plantation where her enslaved relatives once labored. At the ceremony, Tilson helped spread that soil around the new oak, a symbol of her ancestors’ return home.

Thomas Jefferson’s university

In August, white nationalists marched through the University of Virginia campus in Charlottesville, protesting the city’s plan to remove a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. One counter-protestor was killed, and dozens of people were injured.

It wasn’t the first time people in Charlottesville and the University of Virginia have struggled with the legacy of slavery. The school was built by slaves. Its students and faculty were served by slaves. And like Georgetown, the school continues to search for ways to atone.

In 2013 UVA established a commission to examine the institution’s history with slavery. Since then the school has acknowledged its participation in slavery and honored the people it once enslaved. Students helped create a slavery walking tour of the campus. And a prominent stone memorial is planned to honor the estimated 5,000 slaves who labored at the university between 1817 and 1865. Completion of the $6 million Freedom Ring is scheduled for 2019.

Some of the projects have resulted in direct contact between university officials and the descendants of slaves who worked there.

In April UVA President Teresa Sullivan dedicated a new building on campus — Skipwith Hall, commemorating an enslaved stonemason named Peyton Skipwith. It’s located on what’s believed to be the site where stone was quarried to build the original campus, known as the Academical Village.

“This is part of a broad ongoing effort to recognize the role of slavery in the university’s history and to educate the members of our community about the role of the enslaved people at UVA,” Sullivan said at the dedication.

UVA was founded in 1819. It was created and designed by former President Thomas Jefferson with the help of fellow Virginians James Monroe and James Madison.

The school was Thomas Jefferson’s idea. His plantation, Monticello, was nearby. He wanted to create an atmosphere of learning based on reason and exchange across academic disciplines. While most colonial colleges and universities had ties to Christian denominations, Jefferson considered religious belief to be a private matter. He also was especially concerned that so many young southern men went to northern colleges.

Jefferson designed UVA. The centerpiece is the domed Rotunda, meant to evoke the Pantheon of ancient Rome. The university bought a number slaves to work with free black and white laborers. Slaves did all facets of the work, leveling the ground, planing the timber, quarrying the stone and firing the bricks.

“The story of slavery is basically everywhere at the old university,” says Kirt Von Daacke, an assistant dean and a professor of history. “About a million bricks went into building the Rotunda. And every one of them was touched by an enslaved person.”

Jefferson held paradoxical views about slavery. He abhorred the institution, saying it corrupted slave owners, slaves and threatened the new, democratic nation. Yet he owned more than 600 slaves and freed only a handful. And most historians agree that he had six children with his slave, Sally Hemmings.

Von Daacke says that Jefferson’s ambivalence toward slavery can be seen in the design of the Academical Village.

The sleeping and learning quarters are arranged in a long, graceful U-shape, around a rectangular lawn. The rooms are nearly 200 years old, and students covet the chance to live in them. With its arcaded walkways, the lawn was the “white face” of Jefferson’s village, Von Daack says. The working section was the gardens in the back. Slaves lived, worked and grew food there. The design purposely obscured the slaves with brick walls built 8 feet high.

Honoring Peyton Skipwith

Standing on the center lawn of the Academical Village, Von Daacke says Jefferson’s attempt to obscure the “black face” never quite succeeded. “It couldn’t function that way because the enslaved had to cook, serve, clean rooms, paint, dig holes — whatever needed to be done,” Von Daacke says. “This is entirely a space where the enslaved are coming and going all day.”

More than 100 slaves worked on campus at a given time, serving more than 600 students and faculty, records show.

Stonemason Peyton Skipwith was owned by John Hartwell Cocke. Cocke co-founded UVA and was a right-hand-man to Jefferson in building the place. Cocke’s Bremo Plantation lay about 25 miles from Charlottesville.

Cocke and Jefferson shared two controversial beliefs that set them apart from other Virginia plantation owners: that slavery was a deplorable institution that tended to degrade society, and that slavery should eventually be abolished. Unlike Jefferson, Cocke was also a devout Christian. Though it was illegal to do so, he taught many of his slaves to read and write. He wanted them to study the Bible, lead a pious life, and be prepared to succeed when emancipated.

The UVA archives hold a trove of letters between Peyton Skipwith, his niece Lucy Skipwith and their master, Cocke. While most first-hand accounts of life under slavery are memoirs, the letters from Lucy and Peyton are an unusual opportunity to hear enslaved people chronicle their lives in real time. Historian Randall Miller published an anthology of them, “Dear Master, Letters of a Slave Family.”

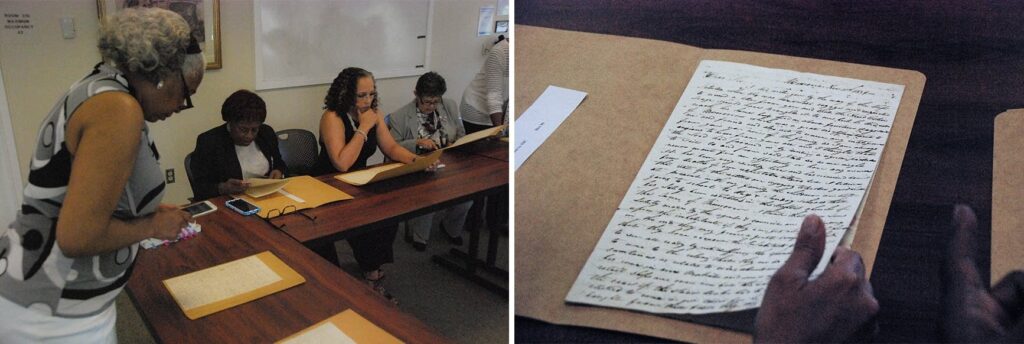

When Skipwith Hall was dedicated, UVA invited Skipwith descendants to speak at the ceremony and to examine original copies of letters by Peyton and Lucy Skipwith. Carol Malone is the great, great granddaughter of Lucy Skipwith and a community activist in Cleveland. She first encountered Lucy’s letters in “Dear Master.” Malone says her ancestor seemed familiar.

“She was able to write and advocate for her family,” Malone says. “And when I read the book, I made sense to myself because all of us family are writers. All of us are advocates and activists in some way.”

The dedication of Skipwith Hall was just one step in a longer process of addressing for slavery at the University of Virginia. In 2015, the school dedicated a new, five-story dormitory for Isabella and William Gibbons, who became prominent members of Charlottesville’s black community after being owned by faculty members.

UVA also runs a week-long summer camp for 30 high school students on the history of slavery. Called the Cornerstone Summer Institute, it was created in 2016 by Von Daacke and Alison Jawetz, a former graduate student. “When students learn about slavery in elementary or high school, it seems very distant and ancient,” Jawetz says. “A camp like this talks about the systematic disadvantages that have accrued to people of color.”

Universities and colleges with ties to slavery will grow stronger by confronting those legacies, says former Brown University President Ruth Simmons. Brown was the first school to meaningfully address that history. In 2003, Simmons appointed a commission to examine the school’s extensive ties to slavery and related industries.

She says today it may be an uncomfortable process for educational institutions, but it’s essential. “If you persist in telling a lie about your origins, you are culpable today, and the public has a right to judge you on that basis,” Simmons says.

The reasons for confronting slave ties are highly practical, as well, she says. The goal is to create more historically aware young people who strive for better lives and stronger bonds with each other. “So not to go back and punish people, but to build on what we know,” she says, “to make sure we have a better future.”