By Katie Donington

Debates over Eric Williams’s work have ebbed and flowed ever since he first published Capitalism and Slavery in 1944. His book inspired a body of historiography to which many historians of slavery and abolition have added their voices over the decades. Scholars working within the Black radical tradition took up Williams’s work, notably Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism, which reinforced and extended Williams’s claims by arguing that slavery and colonization were the foundations of racial capitalism. The recent upsurge of interest within academia of the relationship between capitalism and slavery traces its roots to Williams’s pioneering arguments about the role slavery played in the development of the systems of global capital, industrialization, and the emergence of free trade. Works by Joseph Inikori, Edward Baptist, and Mark Harvey on industrial capitalism, Sven Beckert and Walter Johnson on cotton, and Priya Satia on the gun trade, all draw on frameworks of critical understanding first outlined by Williams. It is a mark of the text’s significance that 76 years after publication we continue to revisit his work and remake our thinking about to it.

Williams’s text has informed my own academic practice and it is a text to which I have returned frequently. I spent many years working with the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at University College London. The project was split into two phases, the first of which used the slavery compensation records to document the enslavers at the end of Caribbean slavery in 1834. The second phase covered the period 1763-1833 and attempted to trace the transference of so-called “property in people” using a far more disparate and therefore less comprehensive set of archives in both Britain and the Caribbean. The project foregrounded Williams’s work by highlighting the ways in which an analysis of these records might contribute to some of the key theses that he set out. In tracing the investments that enslavers made, it has been possible to build up a more detailed empirical picture of the role of slave-based wealth in the formation of British commerce, industry, politics, and culture.

The overall findings of the project supported a modified version of Williams’s claims about the relationship between slavery and industrialization. Some individual stories offer striking examples of his assertions about the role of direct investment. The Greg family, for example, had multiple interests in the business of slavery over several generations. These included provisioning plantations, slave and plantation ownership, the insurance of slave-produced commodities and official government positions in the Caribbean. Samuel Greg was the founder of Quarry Bank Mill in Cheshire. As Sven Beckert has pointed out, Quarry Bank Mill revolutionized the production of cotton goods contributing to the establishment of Manchester and its hinterlands as the Cottonopolis of England. Long after Britain legally abolished slavery, the mills of the northwest continued to import cotton produced by enslaved people from the Americas.

Despite the family’s ongoing ownership of plantations in Dominica, Samuel’s son Robert Hyde Greg advocated for free trade and supported the equalization of the sugar duties. Slavery had offered the family its initial route to commercial success but its shift into industrial production diminished its reliance on slave economy of the Caribbean and offered new opportunities through an engagement with global markets.

More broadly speaking, slave-owners made investments across a range of infrastructure projects including roads, canals, railways and docks, all of which were vital to the expansion of industrial and commercial productivity. The payment of slavery compensation money coincided with the railway boom of the 1840s and so far, the project has identified 160 individual enslavers who bought stocks and shares in railway companies. The Glasgow West India merchant Thomas Dunlop Douglas received almost £16,000 in compensation money for 368 enslaved people held in British Guiana. He invested enormous sums of money in the railways across Scotland. Despite his gargantuan investment portfolio, his will recorded that he left £241,518 to a nephew on his death in 1869.

The project also drew on Williams’s analysis of the role of enslavers as philanthropists and cultural consumers. “The slave traders,” wrote Williams scornfully, “were among the leading humanitarians of their age,” (p. 47). He detailed the benevolent activities of some of the most prominent enslavers in Liverpool including Bryan Blundell and Foster Cunliffe who both contributed large amounts to the establishment of the Bluecoat Hospital, a charity school for poor children. As Williams made clear, participation in the brutal regime of violence which underpinned the system of slavery was no bar to respectability—it was the means to achieve it. Having risen up through the social ranks as a result of success in trade, these newly moneyed men found ways to ennoble their wealth by exercising their power as benefactors and patrons.

This was a claim which has been borne out time and again within the findings of the project. Enslavers emerged as collectors, connoisseurs, members of elite clubs and societies, and the founders of cultural institutions. Britain’s museums and collections have been enriched through the transfiguration of enslaved labour into the signs and symbols of civilisation—art, books and precious objects. Crucially, as Simon Gikandi has argued, the culture of taste also became a central discourse through which hierarchies of race were articulated and reproduced.

Throughout the text Williams’s made reference to another key facet of the structure of both capitalism and slavery which has been at the core of the project—the family. Whilst there was no explicit discussion of the role of family in the making of these systems, Williams highlighted a number of examples of dynastic profiteering (pp. 87-91). Catherine Hall has argued that a lack of attention to the role of gender in histories of capitalism has masked the central role played by women in the establishment and expansion of networks of colonial commerce.

My own work on one of Jamaica’s most powerful planter-merchant family—the Hibberts—has confirmed the necessity of unpicking the complicated web of relations which made up the transatlantic world. Williams identified the Hibberts as a “leading Manchester firm” (p. 71) in a section which explored the key figures in the city’s slave economy. Williams noted, “Between the cotton manufacturers of Manchester and the slave traders there were not the close connections that have already been noted in the case of the shipbuilders of Liverpool” (p. 70). The bonds that tied this community together were intimate—it is only through tracing the marriages made by the Hibbert women that the relationships between the Atlantic merchants and traders of Manchester become clear. Women stood at the nexus of the system of colonial commerce, property ownership, inheritance, and the reproduction of social and economic power.

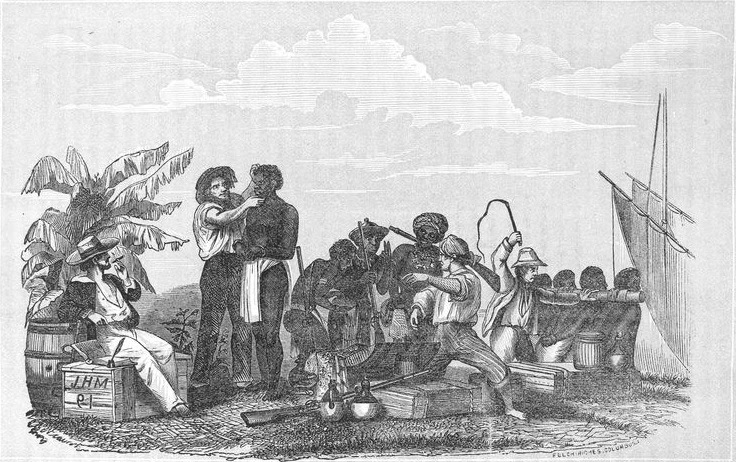

In the closing paragraphs of Williams’s work, he touched on pro-slavery racial ideology’s lasting legacy. As the project documented, those invested in the system went to great lengths to shape its representation and in doing so fix the identity of both the enslavers and the enslaved. They produced pamphlets, books, speeches, and images that did the work of propagandizing their vision of the racial order of things. Edward Long, an enslaver and historian, published his three volume History of Jamaica in 1774. It contained some infamous passages which detailed his extreme views on Africans, including his belief in polygenesis. The History was a huge success and has been reprinted many times over including an online version in 2011.

After slavery ended, these works formed part of the textual and pictorial archives out of which historical memory has been constituted. Williams argued that “the ideas built on these interests continue long after the interests have been destroyed” (p. 211). Divorced from the economic origins to which they were once harnessed, ideas of African inferiority that were used to justify the depredations of slavery continued to circulate. These myths structured the expansion of the British empire and in turn informed racial attitudes which emerged in the wake of post-war migration into Britain from its former colonies.

The process of dismantling the racial mentalities produced through the experience of slavery and colonialism is the unfinished business of abolitionism. In a moment in which projects of right-wing ethno-nationalism are experiencing a global surge in popularity Williams’s words continue to carry weight: “We have to guard not only against these old prejudices but also against the new which are constantly created. No age is exempt” (p. 212).