Why some Black leaders say the time has come

By Steve McKinley

HALIFAX—Lynn Jones has a chart of her family tree on her dining room table. It traces her roots back as far as her great-grandfather Sam Jones, who was enslaved in Kentucky before making his way to Nova Scotia.

The chart flows from Sam Jones — who settled first in the community of Preston, N.S., then in Truro, the transportation hub of Nova Scotia — to her grandfather Jeremiah, to her father Elmer, who would walk the streets a couple of hours before each church meeting, gathering all those who were supposed to attend.

The family tree is resting on a dining room table that’s full of papers — papers for the myriad projects in which Jones is involved.

This is an inheritance from her mother, who used to work the same way, filling the table during the week, but always clearing it for Sunday dinner. Jones used to complain about that as a child; as an adult, she does exactly the same.

One of these piles of paper is her work on reparations.

Jones has been called “the godmother of reparations” by some. When you talk about reparations for Black people in Nova Scotia, Lynn Jones’s name will almost certainly come up.

“Have you talked to Lynn Jones?” people will say. “You should really talk to Lynn Jones.”

Lynn Jones lives in a province where the particular, painful history, and a growing social awareness, are making more people sit up and listen, in a way that could be precedent-setting for Canada.

And she has a lot to say about reparations.

“You have to understand,” said Jones, “the word ‘reparations’ is a political hot potato.”

She’s not wrong. While the idea of identifying historical injustices is palatable to most white Canadians, when the talk turns to redressing those historical wrongs, many of those same people are quick to hit the brakes.

When people talk about reparations, most think about it in financial terms: cash handed to a people or their descendants who have suffered historical injustice.

But money is not the full story of reparations, say Black leaders. Money alone is not going to balance the legacy of 400 years of injustice. What they say they want are the mechanisms to enable Black people to stand on equal footing with white Canadians.

And that means reparations that come in other forms. They come in the form of educational opportunities — of scholarships for families who can’t afford higher education. They come in the form of land titles to enable families to build wealth and equity. They come in the form of representation, both political and academic, so that Black children have mentors on which to set their sights.

This, right now, is the strange part of the conversation.

There’s the shock and horror of watching a white police officer brutally and casually kneeling on a neck, choking a Black man to death in broad daylight in front of cameras.

There’s the eye-widening realization that for Black people, this sort of thing happens all the time.

And then there’s the next stage, the part in which people ask, “Shouldn’t we do something about this?”

This is the part where they almost never say the word “reparations.”

“Reparations,” said Jones, who’s the chair of the Nova Scotia chapter of the Global Afrikan Congress, “is all the things that have happened to us, whether it be the police, the land claims, the anti-Black racism that we see happening. We talk about economics — people’s businesses. We talk about health. All these things relate to what’s happened to us for over 400 years since slavery.

“That’s why it’s all connected, and now is more than ever the opportunity to seek some of the things that we haven’t been able to get.”

The first step, to her mind, is research; the establishment of a reparations centre, a place where paid staff can do Black history research, identify where reparations are needed and plan for pushing ahead with reparation demands.

“In order to achieve the reparations that we require, it’s going to take somebody bigger than me,” she said.

“It’s going to take historians to develop the history of African people and write that with clarity. It’s going to take the politicians (to describe) what happened to us politically. It’s going to take the educators — (to understand) what happened to us in the education system that denied us all these things.”

When Black communities talk about reparations, they’re not only talking about the history of slavery. They’re also talking about the histories of geographic displacement and schooling segregation.

Black settlers in Nova Scotia in the late 1700s, were offered the promise of “freedom and a farm” as a reward for helping British Loyalists fight against the U.S. in the waning days of the American Revolution. When the U.S. won its war of independence, many Brits and more than 3,000 Black people evacuated to Nova Scotia.

There it turned out that the promises they had been made were porous. For many Black people, the land promised was not delivered. For others, Black people were given the poorest of hardscrabble lots to settle — land that would not yield food — and left to starve.

North Preston was one of those communities.

Archival photographs from the 1930s show people standing on the side of dirt roads on a gently rolling land littered with rocks, scrub brush and the occasional stunted tree.

Here, 20 kilometres northeast of Halifax, an entire community of Black people was given land, but no deed and title to it. For successive generations of that community, that meant that they could live on the land and they could pay taxes on it, but they couldn’t legally will it to their children, they couldn’t sell it, and they couldn’t take out a mortgage on it.

It meant that generations of Blacks carved out a life on this impoverished land with the knowledge that it could be taken from them at any time.

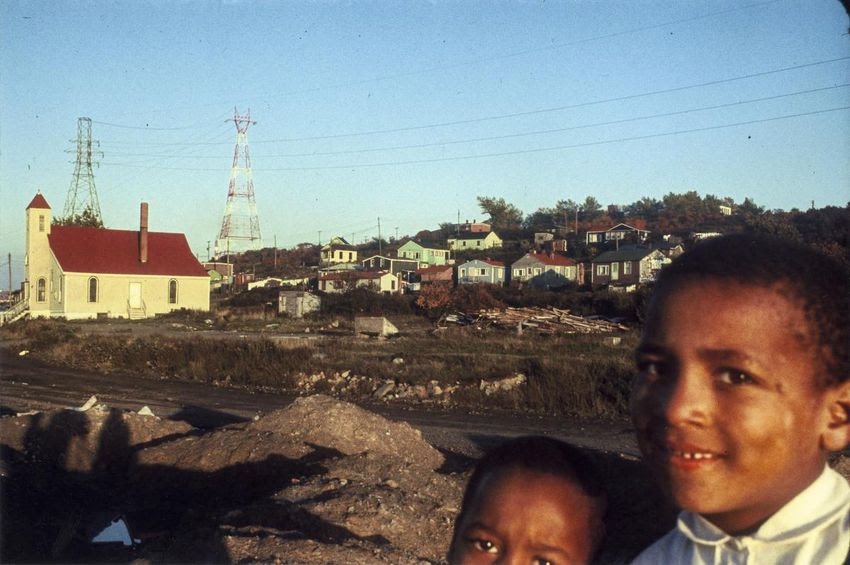

Which is exactly what happened, 20 kilometres away, in Africville.

Africville in Halifax was the only community in Nova Scotia where Black people were able to live on prime real estate near the sea. Black people began to settle there, at the northernmost point of Halifax, on the Bedford Basin in the mid-1800s.

A few hundred people built a thriving community there; fishing and farming, a few small stores, a school, a post office and the Seaview United Baptist Church — the cultural and spiritual heart of the community.

Here the displacement came in waves. First the city ran a railway line through the community, then built slaughterhouses, a prison and an infectious disease hospital, in close proximity, all the while ignoring pleas from the taxpaying residents for basic infrastructure, such as drinkable water, sewage systems, garbage collection and paved roads.

In the 1950s, the city built an open-pit dump near the western edge of Africville.

Shortly after that, after having piled one indignity after another upon the community, in the late ’60s, the city of Halifax declared Africville an uninhabitable slum. It began the process of expropriating land, relocating the residents and bulldozing their homes, sometimes with only a few hours’ notice.

At one point, when the moving company hired by the city cancelled, the city continued to move out residents and their belongings — using dump trucks.

In November 1967, in the middle of the night, Seaview United Baptist Church was destroyed.

The cost of losing land goes much further than just losing hard-won communities.

“We know, because of the gazillion studies that have been done about wealth inequality, that wealth in North America is determined largely by property ownership and the equity that’s gained into property,” said Rachel Zellars, assistant professor in the Social Justice and Community Studies department at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax.

“So when we’re talking about Nova Scotia, and that lack of title and deed, we’re also talking about the intentional impoverishment of Black people over generations. You cannot build a middle-class status unless you own things that acquire equity.”

In much the same way that wealth and social status are handed down through generations, so, too, are poverty and the lack of a place in society.

Black Nova Scotians have suffered the trans-Atlantic slavery trade. Their communities have been displaced and their children for generations have attended inferior schools.

The last segregated school in Canada was in Lincolnville, N.S., in Guysborough County, some 260 kilometres northeast of Halifax. It closed its doors in 1983.

In September of 2017, the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent submitted a report following a visit to Canada the previous year. The first recommendation offered by the Working Group was this: “The Government of Canada should: (a) Issue an apology and consider providing reparations to African Canadians for enslavement and historical injustices.”

Despite mounting pressure from the Black community in Canada, neither an apology nor reparations were forthcoming.

The idea of reparations, in this context, simply means to make amends or atonement for historical wrong or injury, Zellars explained.

“Financial compensation, political representation and educational compensation are typically the three big areas that we advocate for,” she said.

Financial compensation might mean setting aside money for people who were historically wronged. But it could also mean the establishment of a community trust, with the community deciding, for example, to set aside funds for Black youth-led projects, or to buy back properties in Halifax’s North End, which were once owned by the Black community there.

“Financial compensation is not just the idea of putting money into people’s pockets,” said Zellars. “It means thinking about how to create economic wealth and economic self-determination in communities.”

Educational compensation might take the form of scholarships, or the creation of Afrocentric schools.

“Community members have been working for years to make an Afrocentric school — or a school that is specifically for African Nova Scotian kids — a reality here because of that 200-year history of segregated schooling and the way that that has devastated the opportunities for educational advancement,” said Zellars.

Over the past three years, Dalhousie University and King’s College in Halifax have undertaken studies to fully understand their connections to slavery in Nova Scotia, and how those institutions benefited.

Those studies are tied to the issue of reparations in that both schools profited immensely from Black slavery, both in terms of influential figures being connected to the slave trade, and in terms of money coming into the schools from people involved with slavery.

So the demand for reparations for building those institutions on the backs of slaves is educational compensation and representation.

“You owe us, King’s and Dalhousie, via huge chunks of set-aside scholarships for African Nova Scotians so that we can get our kids into these colleges and not have to worry about money,” said Zellars.

“You owe us via representation. We’re demanding that you do a cluster hire of five to 10 Black faculty over the next five years in all of the disciplines so that our children can see themselves and see their histories represented in the expertise of these Black scholars.”

There is some small movement afoot on this front. Although Dalhousie has not committed to doing the cluster hires, it has committed to creating an honours program in Black and African Diaspora Studies, and is putting together a proposal for a research institute for Black Studies in Canada.

Talk about reparations includes one of the defining moments of Halifax and Nova Scotia — the Halifax Explosion of 1917. Last year, researchers documented how Black residents were systematically denied compensation for what they lost and how they suffered in the wake of one of the biggest maritime disasters in history.

But at the same time, those researchers concluded that reparations, while appropriate, likely weren’t on the table.

That’s because Canada just doesn’t have the legal framework to provide redress to the descendants of historical systemic discrimination.

Section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which came into force in 1985, guarantees equality before and under the law on the basis of race, among other grounds.

But, said Mark Culligan, one of the authors of “Racism and Relief Distribution in the Aftermath of the Halifax Explosion,” courts have argued that it is not applicable to discriminatory events pre-1985, when the Charter came into effect.

In addition, said Culligan, human rights legislation, both federal and provincial, have time-limitation periods, thus effectively barring claims regarding historic discriminatory actions.

“I think it’s unlikely that a court is going to order the province to give any worthwhile amounts of money,” said Culligan.

“That’s the essence of the problem. And I think the state is very happy with that because there are many forms of discrimination that have happened through Canadian history, and the state is interested in limiting its liability for that discrimination. Just in the same way that it has to do that today.”

Instead, he said, any type of reparation for the discrimination against Black Nova Scotians following the Halifax Explosion is more likely to achieve success through political pressure than through litigation.

In 1988, the Canadian government offered an apology and a $300 million reparation package for Japanese Canadians who were interned during the Second World War. In 2008 the government established a $10 million fund as reparation for the internment of Ukrainian Canadians who experienced wartime internment.

In both cases, it was a political movement that created enough pressure for reparations to be delivered.

In 2020, in the post-George Floyd examination of systemic anti-Black racism, that time may now be here.

“I think you can’t miss the fact that we’re in the middle of a Black Lives movement,” said Lynn Jones. “That’s front and centre. And reparations is all about Black lives. So you shouldn’t be talking about Black Lives Matter if you’re not (also) talking about reparations.”