In a desperate bid to head off a Scottish Yes vote, David Cameron evoked a mythical British Empire that had given democracy to the poor and freedom to the slaves. Here Ken Olende looks back at what life was really like when Britannia ruled the waves.

The British Empire was the largest ever known. It covered a quarter of the world’s land mass and ruled over a fifth of its population.

As the militant Chartist leader Ernest Jones said in 1851, “On its colonies the sun never sets, but the blood never dries.”

All that remains of that Empire are a few scattered territories such as Gibraltar, the Falkland Islands and the world’s most remote inhabited islands, Tristan da Cunha.

Gordon Brown, who recently re-emerged to promote the union with Scotland, said in 2006, “The days of Britain having to apologise for its colonial history are over.

“We should celebrate much of our past rather than apologise for it.”

The truth is that the empire was won by military conquest and kept by force in the interests of profit.

The empire began to spread beyond the British Isles in the 17th century. In 1609 English and Scots settlers were sent to Ireland to set up the “Plantation of Ulster”.

They developed land either by displacing the natives or making them tenants.

The British, Dutch and French all established themselves in the Caribbean through legalised piracy.

The first British settlers in Virginia, north America, were helped to find and grow food by the local Algonquin people.

But once the settlers became established they declared “perpetual war” on the natives to gain sole control.

They burned villages, uprooted crops and “ethnically cleansed” people.

Poisoned

In 1623 the British arranged a parley with the Algonquin. They served poisoned wine that killed 200 of the natives.

People sometimes forget that English settlers wiped out the natives of eastern north America some two centuries before the US “pioneers”.

Some groups were unfortunate enough to be attacked on both occasions.

The Cherokee, who had lived in the eastern Appalachian Mountains, were forced west by the British and later attacked again by US “manifest destiny”.

The conquest was not all simple. In 1755 British troops were ambushed by 600 native American guerrillas near what is today Pittsburgh.

A thousand died, including General Edward Braddock, the chief of British forces in America.

The natives were allied with the French and it was often the case that one imperial power would come to the aid of rebels against another.

They were never reliable allies.

The colonies first grew tobacco and later sugar—and before long African slaves were providing the labour power. Britain was central to the development of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The money made from it founded many banks and firms that still exist today.

But slavery was resisted at every stage. Thousands of slaves rose up in Jamaica in 1760.

Imperial historian Edward Long dismissed their leader, Tacky, saying he “did not appear to be a man of extraordinary genius”. But the slaves managed to hold down the British army for more than a year.

The British tried to intervene in the largest slave revolt on San Domingo, led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, who had kicked out the French colonists.

But the empire also suffered a humiliating defeat.

The empire’s “moral” switch to anti-slavery was driven by a combination of slave revolts and the changing needs of British capitalism. A section of the ruling class calculated they could make even more profit exploiting workers, and that enforcing the end of the international slave trade could damage their overseas competitors.

Their hypocrisy was obvious. After slavery was banned in the empire in 1833, the owners were compensated, not the slaves.

Property

And these masters were allowed to keep existing slaves because they were “property”.

Once it lost its American colonies, Britain looked to Asia and later Africa. It came to rule India, its “Jewel in the Crown”, in a piecemeal manner at first.

The British East India Company initially took control of areas where it had established trading posts, but was quick to push further inland.

In the process, it undermined existing industry, particularly textiles.

It kept raw Indian cotton for export to Britain’s mills and factories, then flooded the Asian markets with cheap cloth—all in the name of free trade.

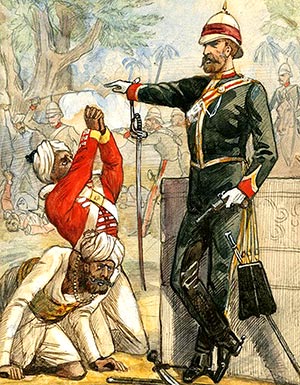

But as with slavery, it wasn’t long before people in India resented British rule and organised against it. Indian soldiers in the British Indian army rose up and turned their guns on their English officers in 1857.

Town after town fell to the rebels and even the capital, Delhi, was captured.

The British were outraged and took brutal revenge. When Delhi eventually returned to British control one imperialist gleefully recounted the callousness of the massacre that followed.

“In some houses 40 and 50 people were hiding. These were not mutineers but residents of the city, who trusted to our well-known mild rule for pardon. I am glad to say they were disappointed,” he boasted.

One British soldier, George Carter Stent, recalled watching the favourite punishment for rebels—being “blown from a gun”. The victim would be strapped with their back against the barrel of a cannon.

“When the gun is fired his head is seen to go straight up in the air some 40 or 50 feet, the arms fly off right and left, high up in the air and fall at perhaps 100 yards distance, the legs drop to the ground beneath the muzzle of the gun and the body is literally blown away altogether,” he reported.

But despite its increasing brutality, the empire could not last.

Fear of more rebellions and rival incursions forced the British to divert an ever greater proportion of what they looted into defending “their territory”.

At the same time new economic powers were emerging that seemed to thrive without the direct control that Britain exerted over its colonies.

Soon these upstarts had the might to challenge the empire and win.

How the age of empire gave way to an epoch of imperialism

The era of colonialism increasingly gave way to a new epoch—imperialism.

In this new world order economic and geopolitical competition combined, as imperialist powers competed to divide the world market among themselves.

It allowed strong states to dominate weaker rivals, and those countries unfortunate enough to constitute the “backyard” of the powerful.

But for the most part ruthless exploitation could be conducted without the need for direct military or political control.

As the Second World War ended Britain’s empire faded.

National movements ensured that the union flag was being lowered across Asia and Africa and being replaced with new emblems of independence.

But the moments of celebration were all too brief.

Within a couple of decades there were new rounds of capitalist crisis and war. These caused carnage and impoverishment, and new ways for the powerful blocs of East and West to gain control.

Now, control of the key economic levers was passed to the IMF and the World Bank, investors from the West, but also China and Russia.

They could demand the privatisation of state assets, the ending of food and fuel subsidies and the slashing of wages.

Countries that refused to bow to their authority quickly found themselves at risk of military action, either from their old colonial masters, or their local henchmen.

This forced all the new states to side with one or another of the imperialist power blocs, and then to follow the rules they laid down.

Rebellion against the old British Empire had meant rising up against colonial masters. Fighting back today means striking a blow not only against the big powers and their capitalist system.

It also means targeting local rulers who are only too quick to enrich themselves at the expense of millions of poor people.

Jon Watson

Monty Python’s ” The life of Brian”, the,”What have the Romans ever done for us” is all the answer needed.

In an era of empires these countries were going to be part of someone’s empire.

Which empire would be best? Ask the he Congolese if they would have preferred the British or no No Belgium?

Or ask the South American nations about how happy they were with the Spanish and Portuguese?

The examples given are exceptions, not the rule and really predate the Empire. These early settlers like the Pilgrim father’s were not intent on building an Empire so much as distancing themselves from Britain and can hardly be taken to represent the values of an Empire. The greatest expansion was a consequence of the Napoleonic wars and more about denying the global resources to Napoleon and his allies.

In one of the “Great Railway Journeys” TV programs from Cape Town North one African woman was asked what she wanted most and she said “I’d like the British back. They were fair. This reflecting that, unlike the French who tried to make everyone into French citizens the British let th live their own lives where possible and that, with independence, there was a return to government along tribal lines which treated the minority tribes badly.

Revolt

To wipe out exploitations and savagery,then it is imperative the social hierarchy and money system must be wiped out.

This was a good article.