April 2016 marks the centenary of the Easter Rising in Dublin, a heroic uprising against the British Empire in its oldest colonial territory.

But this month also marks the bicentenary of an earlier and less well known heroic “Easter rising” against the brutality of imperial domination in another longstanding British colony.

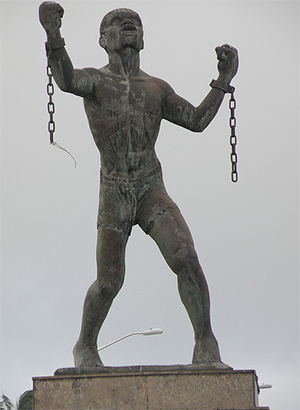

This took place in Barbados in 1816, where it has come to be known as “the Bussa Rebellion” after one of its main leaders. “General Bussa” was an African-born slave who died in the rising and later became a national hero.

The Bussa Rebellion represented the first of a series of notable “late slave revolts” across the British West Indies which were central in finally forcing the British to end colonial slavery across its Empire in 1833.

It saw an uprising spread until over half of the island was engulfed by the insurgency. An estimated 4,000 or so rebel slaves managed to destroy a quarter of the island’s annual sugar crop through arson attacks across 70 plantations.

The bicentenary of the moment in 1807 when Britain ended its formal participation in the barbaric Atlantic slave trade was marked by a huge public programme of events sponsored by the New Labour government.

One of the positive aspects was that it acted as a spur to further serious historical work on the legacies of British slave-ownership. We learnt, for example, that David Cameron’s family—long before the current ‘Panama Papers’ scandal—had a tradition of making obscene riches and profits “offshore”. In this case it was by owning slave-worked sugar plantations in colonial Jamaica.

Slave rebellions against the British received no such public recognition. Yet revolts like those in Barbados in 1816, Demerara (later part of British Guiana) in 1823 and Jamaica in 1831-2 should be remembered and celebrated as a part of working class history.

Abolition

These revolts gave the local colonial master planter class nightmares at the time and also often made an impact in Britain itself. They inspired many in the British movement for the abolition of slavery, and the emerging British working class movement.

The period following 1807’s abolition of the slave trade in the British Caribbean was supposed to be a peaceful one of slow steady transition. There was talk of eventual laws to lift the worst aspects of the barbaric bondage of slavery.

Instead, as historian Michael Craton notes, there was a “rising crescendo of resistance” from the enslaved themselves, with each revolt from below “more extensive, disruptive and influential than the one before”.

Barbados in 1816 was a relatively old and stable British slave colony, whose last revolt had taken place as long ago as 1701.

The ruling planter class existed alongside a tiny white working class, an intermediate group of about 15,000 “free people of colour” (people of mixed African and European descent who were not enslaved) and 77,000 black slaves working on about 400 plantations.

Planters

One important trigger for the revolt came when William Wilberforce succeeded in forcing through a Registry Bill in the British parliament in November 1815. This called for the registration of colonial slaves.

This was bitterly resented by local planter class in Barbados, who feared it as a step which might lead one day to Emancipation and the loss of their slave “property”. The enslaved of Barbados indeed interpreted Wilberforce’s efforts in just such a manner, and now began planning in secret for a rising to secure this Emancipation for themselves “by force”.

As a British colonel who would later interrogate rebel slaves noted, “they maintained to me that the island belonged to them, and not to White Men, whom they proposed to destroy”.

The rebel leaders were mainly an elite of experienced slave drivers, who had been given positions of trust and responsibility by the plantocracy, like Bussa, a “ranger” who was relatively free to travel around the island as part of his work.

Yet as the later “confession” of one rebel slave on the Simmons plantation, Robert, revealed, among the prominent rebel slave leaders was a literate woman, Nanny Grigg, who had been inspired by the Haitian Revolution in the former French colony of Saint Domingue, and had read that all the slaves in Barbados were to be freed on New Year’s Day.

Her key message was that the only way to obtain freedom “was to fight for it, otherwise they would not get it; and the way they were to do, was to set fire”.

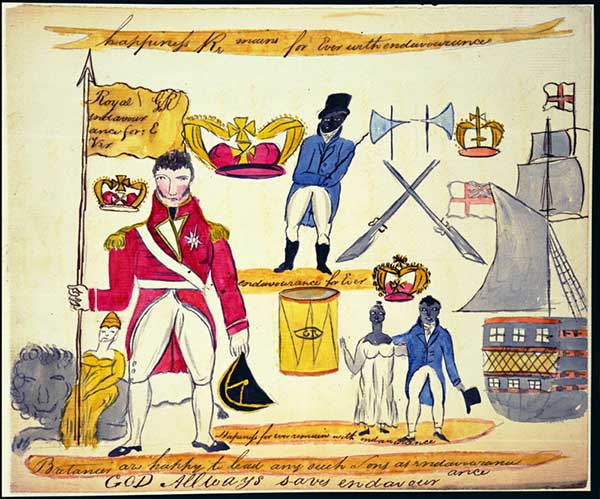

The rebel leaders met on Good Friday, under cover of a dance, and they planned to rise on 17 April. It began prematurely on the evening of Easter Sunday on 14 April 1816 with arson attacks on plantations in the south east of the island which was the signal for a wider uprising.

Militia

While a minority of the free people of colour sided with the rebel slaves, the majority of this intermediate layer in society had not been won to the idea of revolt and instead sided with the white colonial elite as committed members of the local militia, itself about 4,000 strong. The local British West India Regiment—itself in large part composed of black troops, which led to a degree of confusion on the part of the rebels—also swung into action.

The rebel slaves, mostly armed only with pitchforks, soon found themselves outgunned and outnumbered and were forced to retreat.

Within three days, “order” had been more or less bloodily restored. Only two whites had been killed in the fighting, as the slaves had just damaged property and plundered, but the counter-revolution was far more merciless and ruthless. As one British rear admiral later noted, “under the irritation of the Moment and exasperated at the atrocity of the Insurgents, some of the Militia of the Parishes in Insurrection were induced to use their Arms rather too indiscriminately in pursuit of the Fugitives” and “put many Men, Women and Children to Death, I fear without much discrimination”.

Contemporary estimates suggest perhaps 1,000 slaves were killed. We know 144 rebels were publicly executed in the aftermath, 170 were deported and there were innumerable floggings and the torture of captives to extract confessions.

The brutality and vindictive nature of the counter-revolutionary violence led one white Barbadian to report in June 1816 that “the disposition of the Slaves in general is very bad. They are sullen and sulky and seem to cherish feelings of deep revenge. We hold the West Indies by a very precarious Tenure, that of military strength only…”

Today the names of the once famous planters and generals who repressed the revolt are rightly forgotten in the public consciousness, while the inspirational fighters against colonial slavery such as General Bussa and Nanny Grigg are finally beginning to get the belated recognition, attention and honour they deserve.