Africans resisted slavery at every point. There were rebellions on board the ships that carried them across the oceans, which often resulted in the cruelest retaliation. But it was on the plantations that the most serious challenges to the slave economy took place.

The most important of these revolts occurred on 14 August 1791 in Saint Domingue, the French colony that would become Haiti.

Saint Domingue was among the richest places on earth, producing sugar, coffee, cotton, indigo and tobacco. The value of its exports made up two thirds of the gross national product of France.

The 1791 rebellion saw the plantation mansions put to fire and the masters slaughtered. It was led by Toussaint, a coachman slave who had been taught to read and write. He later took the second name L’Ouverture – meaning “the opening” to liberty.

The uprising freed the slaves from their masters and within months Toussaint’s army had captured all the ports on the north of the island.

Toussaint realised very quickly that negotiations with the former slave owners were useless – messengers sent to mediate were often executed before they could even speak.

All this took place during the turbulent early years of the French Revolution. The revolutionaries in France debated the future of the slavery in its colonies. They knew that most plantation owners were royalists and declared the new republic to be against the “aristocracy of the skin”.

In 1794 three delegates from Saint Domingue took their place in the French convention, to rapturous applause. They were a freed black slave, a mulatto (mixed race) and a white man.

Meanwhile the British ruling class was plotting. With the French largely displaced, they hoped to take the colony of Saint Domingue for themselves – and sent the Royal Navy to put down Toussaint’s rising.

Four years later in 1798, the British were routed and Toussaint led his victorious army into Port-au-Prince. The British had lost 80,000 men. It was one of the greatest military disasters in British history.

The British sent more soldiers to put down the rising in the West Indies than it had to suppress North American rebels 20 years previously. Of the nearly 89,000 white officers and enlisted men who served in campaign, some 45,000 died in battles or from wounds and disease. Proportionally, this would be as if the US had lost more than 1.4 million soldiers in a far away conflict today.

By now the revolutionary wave in France had receded and the new rulers wanted to restore slavery. They encouraged a civil war on the island, from which Toussaint again emerged victorious. But the slave army soon faced yet another ruler of France – Napoleon Bonaparte.

Napoleon sent a huge expedition force to put down the rising once and for all. But within the first six months of 1802 the French lost 10,000 men.

On 7 June 1802 the beleaguered generals offered Toussaint a treaty if he would appear in person to discuss it. He did so, was captured and died in a freezing French jail.

But to the astonishment of the generals, the slave army continued to fight and ultimately drove the French from the island forever. Saint Domingue renamed itself Haiti and declared independence from France in 1804.

Less than 30 years later in 1831, it was a rebellion in Jamaica that finally put an end to slavery in British colonies in the West Indies.

Some 60,000 rebels used an underground network based around the Baptist church to coordinate their action. The signal for the rising came on 27 December with the burning of sugar cane trash on the Kensington estate. Once lit, the fires spread from one estate to another until the entire island was covered.

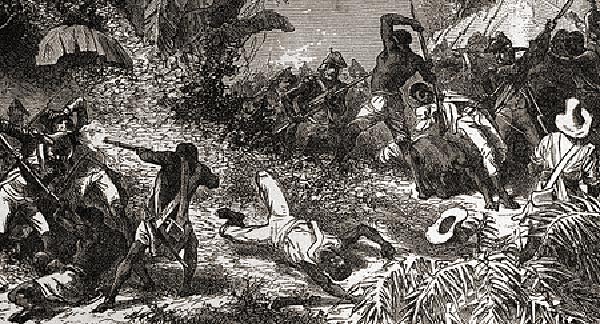

In the rocky hills of Jamaica’s interior lived the Maroons – a community of black people who had gained freedom from slavery. When the British army arrested a number of their leaders, they too joined the rebellion. Fighting as guerrillas from natural fortifications, they killed hundreds of British soldiers.

The boatloads of ragged British survivors that made it home brought news of the senseless waste of life. Some brought other stories – of the misery of slavery and of black people fighting to free themselves from it.

Henry Bleby, a British Methodist minister, said of the revolt, “The spirit of freedom had been so widely diffused that if the abolition of slavery were not speedily effected by the peaceable method of legislative enactment, the slaves would assuredly take the matter into their own hands, and bring their bondage to a violent and bloody termination.”

The realisation that it would not be possible to continually suppress slave revolts hammered down the last nail in the coffin of British Caribbean slavery.