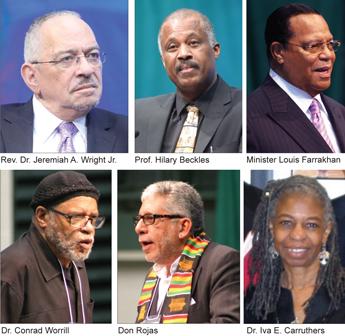

Freedom cannot be compromised Nation of Islam minister tells a Chicago gathering focused on justice for the descendants of survivors, victims of trans-Atlantic slave trade

The Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan told a group of political leaders, researchers and activists that true commitment and a firm unwavering demand for real justice is required, if the call for reparations is ever to be taken seriously by the governments of the earth.

“Nothing is more important than the liberation of our people,” Minister Farrakhan told those gathered at the Emil Jones Convocation Center on the campus of Chicago State University April 19. “If you really want freedom, you cannot compromise with slave makers, slave masters and the collaborators,” he said.

Although he had not been feeling his best, the Minister wanted to be with the “thinkers, warriors and soldiers” in the fight for the reparations and the liberation of oppressed people all over the world.

“We have a responsibility to our ancestors,” said Minister Farrakhan during remarks lasting about 30 minutes. “What kind of generation will we be to have ancestors that have gone through what our ancestors have gone through and we’re sitting here today talking about the revitalization of a movement that should never have had to be revitalized?” he asked.

The meticulous research and documentation of scholars lays the base for movements to build upon and propels movements forward, noted Min. Farrakhan. “You cannot proceed for justice on assumptions. You can proceed for justice on actual facts.”

“When they speak—we act! It is not about applause, it is about acting now because the talk has been done and we talk too damn much and we do too little towards our own liberation!” said the Minister. Revitalization suggests some have lost the spirit of reparatory justice, but, this it is not a quick and easy journey, it is a lifelong struggle until justice is achieved, he noted. Part of the problem is the weak approach of those sometimes sent to speak for the oppressed but who really desire favor with an enemy who only makes promises to deceive and never honors agreements, Min. Farrakhan added.

“When you talk to power, you can’t go to power just with a cry for justice; you’ve got to have power backing your cry! You should never think that the enemy is going to give you the justice that you seek. We’ve been crying at his feet for too damn long! We’ve got to have the power to force justice!”

Cowards will always need revitalization and slaves always want to be accepted by their former slave masters, he added. White governments know the truth about what they did during the slave trade and continue to reject the call for reparations from their former slaves, he said. “What is our response? To go back and beg some more? That’s what got you in the shape you are in! You’re litigating your damn self into poverty and want! It’s not litigation it is revolution that is needed!” the Minister thundered.

Only men and women who aren’t afraid to die for reparatory justice and who are not seeking the friendship of their former slave masters will remain steadfast, he said.

Calling European governments “criminals,” the Minister said he realizes strong talk scares those who aren’t courageous and fully committed. But, he continued, the time has arrived for direct talk about the Black condition and what is required to change it.

“The situation is radical and it needs a radical solution,” said the Minister. “I’m not leaving the Earth as a squirming punk! I speak for the dead who have no voice today! I speak for the living who are voiceless! I speak for the unborn generations who need a voice! That’s the kind of men and women that will make reparatory justice real.”

Observers and activists agreed that the reparations movement in the United States has continuously hovered between lifeless and moribund for the last decade. Many key movement leaders, such as Hannibal Afrik, Imari Obadele and recently Chokwe Lumumba, have died. There have been real questions as to whether the reparations movement is even viable, or, simply an anachronism that has aged along with its leaders.

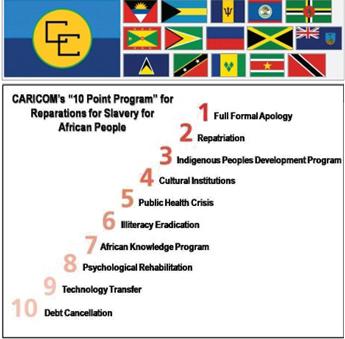

But in early March, the heads of the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) met in St. Vincent and the Grenadines and heavily discussed reparations for a global crime against humanity—the African slave trade. The governments of Britain, France and the Netherlands are primarily being targeted to pay compensation to Blacks throughout the African Diaspora hurt and destroyed by what is commonly called the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Dr. Ralph Gonsalves, prime minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, has been at the forefront of the CARICOM effort. He was scheduled to be the day’s keynote speaker but was unable to make it. In his stead was Rhonda King, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines ambassador to the United Nations, and Professor Hilary Beckles, who serves as chair of the CARICOM Reparations Commission. Mr. Beckles, pro vice chancellor of the Cave Hill Campus of the University of the West Indies, wrote the book “Britain’s Black Debt: Reparations for Caribbean Slavery and Native Genocide.”

The trading of enslaved Africans lies at the foundation of the wealth inequality that exists not only in the United States but worldwide. The Western world was built through the work done, and profits generated by Blacks scattered across the globe and deposited wherever free labor was required by Europeans. Calling reparatory justice “the greatest political movement of the 21st century,” Prof. Beckles explained reparations from responsible governments is more than just economics and finances—though both are important. It is a matter of pride, dignity, and self-respect for the victims of the slave trade to seek reparatory justice for the harm done, he said.

He went over a 10-point plan covering all aspects of what is needed for reparatory justice—ranging from formal apology, to curbing an “explosion of chronic diseases,” such as hypertension and diabetes, which grips Blacks in the Caribbean and the U.S., to debt cancellation.

There has been some tacit and direct admission of wrongdoing by European nations in recent years: The British agreed to issue a “statement of regret” and award $21.5 million to surviving Kenyans detained and tortured during the Mau Mau rebellion decades ago. In 2007 to mark the 200th anniversary of the British prohibition of slavery, then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair “expressed regret” for suffering caused by Britain’s role in the slave trade.

The Haitian revolution of January 1, 1804 effectively ended slavery in that territory, but the equivalent of economic sanctions was used against Haiti as a penalty for her successful efforts at throwing off the chains of slavery and colonialism. Following the January 2010 earthquake, then French President Nicolas Sarkozy reportedly acknowledged the “wounds of colonization,” and quickly approved a financial aid package said to include millions in budgetary support for the Haitian government.

Activists say a mere “statement of regret” will not be sufficient for the horrific trafficking and enslavement of Black human beings around the world. “It is a global struggle for a global crime,” said Prof. Beckles. “They must be held accountable for it. Our plan is to call for that justice.” If they do not respond to the request for justice, these Western European nations will be taken to the International Court at the Hague, said activists.

“Slavery is over, but we are now in the jet stream of the consequences,” said Prof. Beckles.

During brief comments, Rev. Dr. Jeremiah A. Wright, pastor emeritus of Trinity United Church of Christ, said although it is a term widely used in activist and academic circles, he feels it is inaccurate to refer to a trans-Atlantic slave trade because “the Atlantic Ocean never enslaved anyone.” The slave trade was a European endeavor, he said.

Dr. Conrad Worrill, a stalwart in the reparations movement, said no matter what happens, Africans in America and abroad must continue to fight for reparations.

“There is no statute of limitations on crimes against humanity,” said Dr. Worrill, of the Center for Inner City Studies, who helped organize the Chicago State forum alongside Dr. Ron Daniels of the Institute for the Black World 21st Century. Dr. Worrill was also among those who traveled to Durban, South Africa for the World Conference Against Racism in 2001. He witnessed Israel and the United States walk out of the conference when the question of reparations was brought up. While returning to the U.S. to discuss what took place in South Africa, the World Trade Center attack Sept. 11, refocused attention and changed the global landscape activists found. While many continued to fight to keep reparations in public view, the movement struggled to attract the masses of the people, especially young people. Despite the challenges, said Dr. Worrill, those who truly want justice cannot be weak in their call for justice.

“A strong people will never give up fighting for justice and repair from those who damaged you,” he said. Rep. John Conyers, Jr., who first introduced HR-40, the Reparation’s Study Bill, in 1989, vowed to continue to pursue the legislation no matter how long it takes. He first introduced the bill in the 101st Congress of the United States. It is now the 113th Congress. “This is one of the most important pieces of legislations I have ever produced,” Rep. Conyers told the audience.

A global struggle, a global crime

Don Rojas, communications director for the Institute of the Black World, said President Obama has recently talked about income and wealth disparity. That discussion represents an “intellectual paradigm shift,” said Mr. Rojas, who also served as press secretary for the late Grenada Prime Minister Maurice Bishop. The revolutionary was removed from power and executed in a mercenary coup orchestrated by political rivals and Western nations before a U.S. invasion of the small country in 1983.

The reparations movement is “the great moral imperative of our time” and those who line up against it, or perhaps think it is a misguided waste of effort, are “ignorant of the moral power of an idea whose time has come,” argued Mr. Rojas.

Dr. Iva E. Carruthers, general secretary of the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, Inc., an ecumenical group that represents a cross section of progressive Black faith leaders across the country, called the April 19 gathering a “sacred assembly.” The Proctor Conference also helped organize the Chicago State program.

“When you call a sacred assembly, you have to take the risk of hearing from the prophets, and when prophets speak, it may not be comfortable,” said Dr. Carruthers. “I think we were in the hands of master prophets in the form of Minister Louis Farrakhan and Reverend Dr. Jeremiah Wright and I think we’re in the hands of a master teacher in the form of Dr. Beckles. And if we listen to our prophets and our teachers—if we would just be still enough to feel the power of God and the righteous authority upon which we stand to speak truth, to stand on truth and to organize ourselves at any cost with those who share the vision—then this day will be fulfilled.”

Dr. Kelly Harris, director of Chicago State University’s African-American Studies Dept., enjoyed the perspectives offered by Min. Farrakhan and Prof. Beckles.

“Minister Farrakhan really gave us the charge tonight and Professor Beckles was excellent,” said Dr. Harris. “I think Minister Farrakhan did what he always does, he made sure that we stood up and had steel in our back and that’s what we need.”

Dr. Ron Daniels called the mission of the gathering a success as the goal was to “give a spark and deliver a jolt” to the U.S.-based reparations movement. Since there’s power in the fact that Caribbean nations unanimously agreed to the 10-point program, there is now added power, he said.

According to Dr. Daniels, the Institute of the Black World is creating a reparations resource center on its website and will continue to help educate the public on reparations. Asked about the next generation of leaders for the movement, Dr. Daniels said that remains to be seen, but agreed “there’s a need for new blood.”

“We have to see who emerges,” said Dr. Daniels. “Like anything else you have a wave, the people who are involved in it, they tire, they thin, they pass on. The question is will there be someone to pass the torch on to? So I think we need to be focusing on increasingly going at young people; teaching them, giving them history, giving them the background so they can pick up the torch and become the new wave because we need some new troops, but we also need to change the mentality. We need to be able to use some economic sanctions and other modalities to let people know we’re not playing.”

“We have to go to the universities and get them. It is there where—especially young Black men—see the contradictions, they see the differences. If there’s not massive change … even with the education they’re seeing, that’s not a ticket to a lifestyle that they’ve been promised,” said Kamm Howard of the National Coalition of Blacks For Reparations in America, or N’COBRA.

“I think once we build the connections on the university campuses with our young brothers and sisters who can also speak the language of the streets—because a lot of them are coming from the streets and that’s their ticket out—then we can begin to build a movement among the youth. We’re seeing the young people are interested … they’re asking what they can do because they’re looking for some guidance.”

Minister Farrakhan “put it in plain English” that this is a revolutionary struggle that must be fought if the current generation cares about the sacrifices of their ancestors, Mr. Howard continued. “We have to be able to stand before our ancestors and say ‘I fought for this life that you made sure that I have.’ But are we deserving of this life? And if we say we are deserving of it then we must fight to ensure that our future generations have a better life than we had.”