“John Brown’s body lies a-mouldrin’in the grave, John Brown’s body lies a-mouldrin’in the grave, John Brown’s body lies a-mouldrin’in the grave, But his soul goes marching on.”

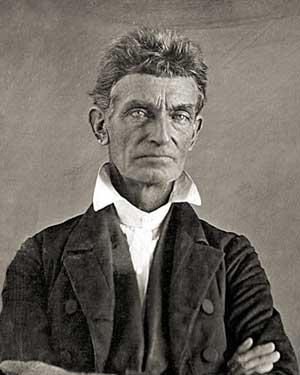

THE MARCHING song “John Brown’s Body” came from the time of the American Civil War in 1861-5. It is still sung in school playgrounds today. But who was John Brown and what did he stand for?

SOME 140 years ago white enemy of slavery John Brown stood in the dock of a Virginia courtroom, knowing that Southern slaveholders were certain to pass the death sentence on him. A month earlier, in October 1859, Brown and a band of conspirators had been captured at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, by US troops. In a daring raid Brown had seized the federal arsenal and armoury at Harper’s Ferry. It lay on the edge of the “Great Black Way”. This was the swathe of slaveholding states that stretched away to the south, holding three to four million blacks in bondage.

Brown had hoped that his actions would trigger a slave insurrection, that slaves would flock to Harper’s Ferry where he could arm them and draw them away to freedom. Although he failed, Brown set in motion the forces that would lead to the civil war two years later. This would end in the defeat of the South and the freeing of the slaves.

At his trial Brown-who had been seriously wounded and spent much of the time laid on a wooden pallet-was wholly unrepentant. In an electrifying speech the deeply religious 59 year old declared, “I believe that to have interfered as I have done in behalf of His despised poor is no wrong, but right. Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I say let it be done.”

On 2 December 1859 Brown was led to the scaffold and hanged along with four co-conspirators. Two of them, Shields Green and John Copeland, were black. In a revealing act of cruelty, the Virginian court had the black men’s bodies delivered to a medical college for students to dissect. Commentators, both North and South, tried to dismiss Harper’s Ferry as the work of a lone madman. But this was not so. In fact Brown was well known in abolitionist circles. His raid was secretly backed by leading figures.

JOHN BROWN had been an abolitionist for around 20 years before the raid on the Harper’s Ferry armoury. The Southern US economy had rested on slave labour for over 100 years. As black historian W E B Du Bois wrote, “American slavery was the foulest and filthiest blot on 19th century civilisation. Four things make life worthy to most men: to move, to know, to love, to aspire. None of this was for Negro slaves. No black slave could legally learn to write. And love? If a black slave loved a lass, there was not a white man from the Potomac to the Rio Grande that could not prostitute her to his lust.”

At first Brown helped escaped slaves flee to Canada on what was known as the Underground Railway. This network would pass runaway slaves from town to town until they were safe. But Brown’s hatred of everything the South stood for was intensifying. He started to think about ways he could strike a telling blow for black freedom.

In 1847 Brown made contact with ex-slave and black leader Frederick Douglass, who described the meeting in his autobiography: “Captain Brown denounced slavery in look and language fierce and bitter, thought that slave holders had forfeited their right to live, that the slaves had the right to gain their liberty in any way they could, did not believe that moral suasion would ever liberate the slave, or that political action would abolish the system.”

Brown told Douglass that he wanted to extend the Underground Railway “by running off larger bodies of slaves”. Douglass was not convinced the plan would work, but Brown had a profound effect on him. He wrote that “while I continued to write and speak against slavery, I became all the same less hopeful of its peaceful abolition. My utterances became more and more tinged by the colour of this man’s strong impressions.”

Douglass was right to be less hopeful of a swift, bloodless end to slavery. Two legal decisions passed in the 1850s strengthened the slavers’ hand across the whole of the US. The Fugitive Slave Act allowed gangs from the South to pursue escaped slaves into the “free states” of the North. The Dred Scott decision declared that free blacks, even in the North, could not become US citizens.

The Southern ruling class was determined to spread slavery to other states in the Union. In 1820 Missouri had gone the way of slavery, followed by Texas in 1840. But the drive to turn the western territory of Kansas into a slave state in 1854 had the most profound consequences. The abolitionists were not the only ones who were furious.

Northern industrialists and politicians, many of whom who felt no strong desire to free the slaves, were enraged that the South was trying to steal territory they wanted for their own. Southern “border ruffians” poured into Kansas in 1855. They hoped to outnumber Northern voters in a crucial election and make Kansas a slave state. A shooting war broke out. John Brown, with a number of his sons and supporters, rode into Kansas. In a revenge attack he kidnapped some border ruffians at Pottawatomie.

As Du Bois writes in his biography of Brown, the captives “were led quickly into the woods and surrounded. John Brown raised his hand and at the signal the victims were hacked to death with broadswords.” Du Bois goes on, “To this day men differ as to the effect of John Brown’s blow. “Some say it freed Kansas, while others say it plunged the land back into civil war. Truth lies in both statements. The blow freed Kansas by plunging it into civil war, and compelling men to fight for freedom which they had vainly hoped to gain by political expediency.”

Brown disappeared from sight. For the next three years he studied military tactics and past slave revolts, especially the successful 1791 slave revolt in Haiti. Brown was secretly backed by “respectable” Northern abolitionists who were desperate for a blow against the South. With the cash Brown bought pikes and rifles. He tried to persuade Frederick Douglass, whose name was known to all slaves, to join him. But the abolitionist warned Brown that he would “never get out alive”.

Brown called a conference of black activists in Canada. He set out a new Declaration of Independence-“That the Slaves are, and of right ought to be as free and independent as the unchangeable Law of God requires that All Men shall be.” On Sunday 16 October 1859 Brown and 22 others began their raid. They captured the federal armoury and arsenal. Tragically, Brown allowed himself to be surrounded and pinned down. In the shootout Brown’s forces were totally overwhelmed. Many of them were killed, including two of Brown’s sons.

Upon capture Brown told his captors, “I want you to understand that I respect the rights of the poorest and the weakest of coloured people, oppressed by the slave system, just as much as I do those of the most wealthy and powerful.” In many Northern communities on the day of Brown’s execution “church bells tolled; guns fired solemn salutes; ministers preached sermons of commemoration; thousands sat bowed in silent reverence for the martyr of liberty.” One journalist wrote, “A feeling of deep and sorrowful indignation seems to possess the masses.”

And as Frederick Douglass later declared, “If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery he did, at least, begin the war that ended slavery. Until this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy, and uncertain.”