In a suburb of Chicago, the world’s first government-funded slavery reparations programme is beginning. Robin Rue Simmons helped make it happen – but her victory has been more than 200 years in the making

by Kris Manjapra

It began with an email. On an especially cold day in Evanston, Illinois, in February 2019, Robin Rue Simmons, 43 years old and two years into her first term as alderman for the city’s historically Black 5th ward, sent an email whose effects would eventually make US history. The message to the nine-member equity and empowerment commission of the Evanston city council started with a disarmingly matter-of-fact heading: “Because ‘reparations’ makes people uncomfortable.”

She continued:

Hello Equity Commission,

thank you for the work you are doing. You have the most difficult work of all the commissions because the goal seems impossible … I realize that no 1 policy or proclamation can repair the damage done to Black families in this 400th year of African American resilience. I’d like to pursue policy and actions as radical as the radical policies that got us to this point.

Simmons went on to invite the equity commission to join her in exploring “best actions” and pursuing “the light at the end of the tunnel”. The email, five paragraphs and 350 words long, was a spark. By November 2019, Robin Rue Simmons had successfully inaugurated the US’s – and the world’s – first ever government-funded slavery reparations programme.

Evanston is a majority-white university town about 13 miles north of Chicago on the shores of Lake Michigan. From the turn of the 20th century, Black families began arriving in Evanston in large numbers. Around 1915, the process grew into the great migration, one of the greatest internal population movements in modern American history. Over a period of decades, some 6 million Black people left the post-plantation south to fill the growing labour vacuum across the industrial north, and to escape intensifying white supremacist campaigns for retribution and racial rule. These campaigns and policies, collectively called “Jim Crow”, included voter suppression, police brutality and mass incarceration, segregation and the terror of lynching.

Yet the shadow of Jim Crow followed Black families northward, westward and eastward as they migrated. “The negro population of north shore towns [is] steadily increasing, and in Evanston the newcomers are deemed especially objectionable,” reported an article from the Chicago Daily Tribune in 1904. “As a solution of the problem, Evanston citizens are reviving the old scheme of a town for negroes.”

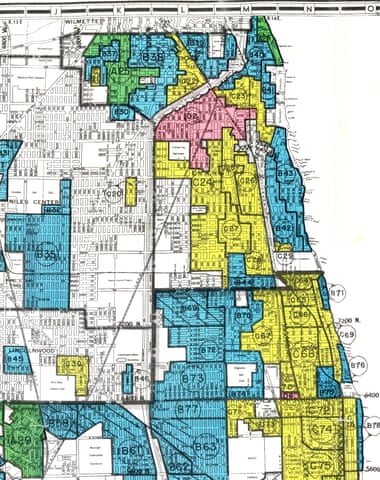

FacebookTwitterPinterest A ‘redlining’ map of Evanston issued in 1940. Photograph: Robert K Nelson/University of Richmond/National Archives

In 1919, with a Black population of 2,500 in a city of 37,000, the Evanston city council created a new triangular zone bounding the Black residential enclave located in the city’s inner core. The zone was tagged for disinvestment: there would be no development of schools, parks, playgrounds, libraries or grocery stores. As documented by the Shorefront Legacy Center, the city’s racial zoning policy was soon complemented by discriminatory realty and housing practices. Starting in the 1920s, real estate agents wrote “restrictive covenants” into house deeds, limiting the resale of properties in “good neighborhoods” to “Caucasians only”. Housing segregation grew more intense during the 30s, when the federal government introduced “redlining maps” for US cities. Neighbourhoods across the nation were graded according to their supposed lending risk for banks. In 1930s Evanston, the 5th ward, home to 95% of the city’s Black population, was graded as “grade D: hazardous; home to an undesirable population”. By the 40s, based on redlining guidelines, banks had largely stopped providing loans to Black families.

And by the 60s, according to estimates by sociologists, Evanston was one of the most segregated cities in the US. In the early 90s, accusations of racist business practices led to two federal lawsuits against Evanston real estate firms. Recent data shows an ongoing story of disinvestment. In 2019, banks offered 1,487 mortgages to homebuyers in Evanston. Only 95 of those went to Black customers. Nationwide, Black families owned fewer homes in 2018 than they did 30 years ago. The wealth gap separating Black families from their white peers has grown exponentially during this same 30-year period.

Having grown up in Evanston’s 5th ward in the 80s, Simmons knows this story personally. When she reached third grade, she transitioned from a Black church school to a regular public school. Since the ward had no public schools, that meant a daily commute. “Evanston is a small city, so [school] wasn’t far, but it wasn’t in my neighbourhood,” she told me recently. “I don’t think the bus came to our neighbourhood.” Instead, her grandfather dropped her off at school every day in his paint contractor’s van – something she loved, especially when she got to sit atop the five-gallon bucket in the back.

Even though her neighbourhood had no public school, no grocery store, few parks and no access to Evanston’s lakefront, Simmons grew to cherish what the Black community had created here, amid this infrastructure of enforced deprivation. As a high school senior and head of the student government, Simmons was already on the speaker’s circuit of local Black churches. “The church is something I was introduced to early on, in order to navigate a system where there are barriers around you no matter how hard you work,” she said.

When Simmons was 19, her family had to sell their home to pay for her grandmother’s cancer treatment. There were no other family assets available. Structural racism and discrimination conspire to drain Black families of wealth, preventing them from creating financial safety nets that can span generations. Black people know what it’s like, generation after generation, to confront the racial wealth gap as they start all over again. After losing her beloved grandmother, Simmons did just that. “My story is not about being downtrodden, but underresourced,” she told me. Simmons began college while working at the mall to make ends meet. By 22, she obtained her real estate licence and started a general contracting business. Eventually, she became a property developer focused on building affordable housing in Evanston, and entered elected office in 2017, aged 41.

Today, the average income of Black families in Evanston is $46,000 less than that of white families; Black people’s life expectancy is 13 years shorter than for white people. And more than 60% of all people arrested in Evanston are Black, even though they represent just 16% of the population. Robin Rue Simmons, like all reparationists before her, believes that “something just as radical” as the harm itself is needed as remedy.

In June 2019, Simmons and the equity commission launched a “solutions only” reparations plan focused on addressing the economic damage done to Black residents by Evanston’s history of redlining, racial zoning and discrimination by banks and real estate firms. Simmons began a series of community consultations with hundreds of Black Evanstonians. The meetings led her to propose $25,000 grants to eligible Black homebuyers in Evanston, along with additional funds to assist Black homeowners in paying property taxes and completing home renovations. The community also asked for the creation of the first-ever public school in ward five.