People across the political spectrum acknowledge that racism exists, but its origins are shrouded in mystery—deliberately so.

Racism is presented as if it has always existed, and individuals make a personal choice to be racist.

In reality racism was developed as a means of justifying the transatlantic slave trade, which was crucial for the birth of industrial capitalism.

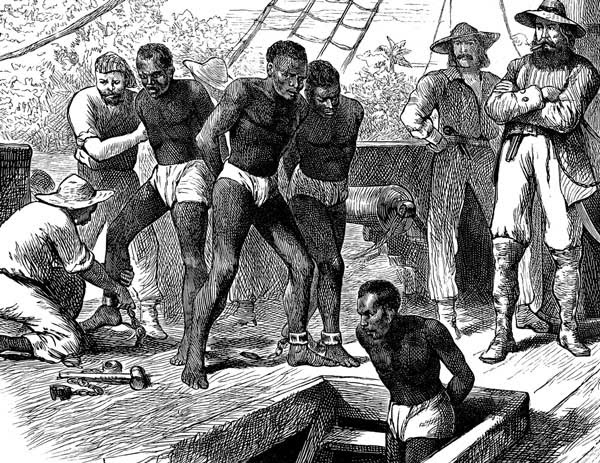

According to one account of the “middle passage”—the journey across the Atlantic—the “height, sometimes, between decks, was only 18 inches.

“The unfortunate human beings could not turn around, or even on their sides, the elevation being less than the breadth of their shoulders.

“And here they are usually chained to the decks by the neck and legs. In such a place the sense of misery and suffocation is so great.”

Another account described the slave decks as “so covered with blood and mucus that it resembled a slaughterhouse”.

People killed each other to breathe, others threw themselves overboard to end their suffering.

For capitalists their profits were justification enough, but all this was publicly justified with the doctrine of “scientific” racism.

By claiming that Africans were subhuman, it was designed to nullify the slavers’ crimes.

Other forms of slave society existed before the transatlantic slave trade. Despite their brutality, these were organised on a very different basis. There was no division based on skin colour or “race”.

In Ancient Greece there was a division between the “civilised” and the “barbarian”, a distinction which had nothing to do with race.

According to the historian Anthony Pagden “a barbarian was, before anything else… one who spoke not Greek but only ‘barbar’”. It was therefore possible to move across the divisions by learning the Greek language.

But “scientific” racism changed the rules by claiming there was something innate in black people that made them less than human.

Even during the early stages of the transatlantic slave trade in the 16th century, ways of justifying the enslavement of other people came after the fact.

Theological debates simmered while the conquistadors laid waste to South America.

When priests decided that slaves could be converted to Catholicism and released, they set off to the colonies only to be thrown overboard en route.

Spanish and Portuguese slavers were plundering riches from the colonies that were too valuable to relinquish.

A new merchant class was funding the wars of the feudal rulers of Spain and Portugal with blood-soaked gold and silver from South America.

Capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.

– Karl Marx

There were tensions between these old and new worlds.

But they could coexist for the time being, especially with so much wealth to ease the friction.

Spanish emperor Charles V only stepped in to place limits on the bloodletting in 1542 after millions had died through murder and disease.

Even then he did not outlaw slavery outright. People from Africa continued to be transported.

Britain’s entry into the slave trade in around 1670 meant that it changed. It became an industrial operation.

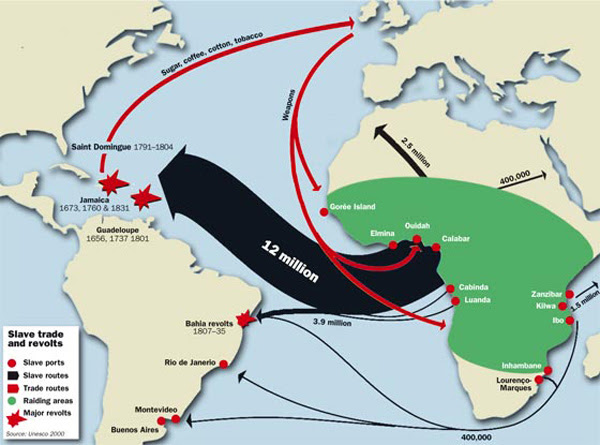

In the first half of the 17th century, some 370,000 people were taken from Africa to the Americas as slaves. In the latter half, just under one million were transported. At the peak, over 3.5 million were transported over the course of 50 years.

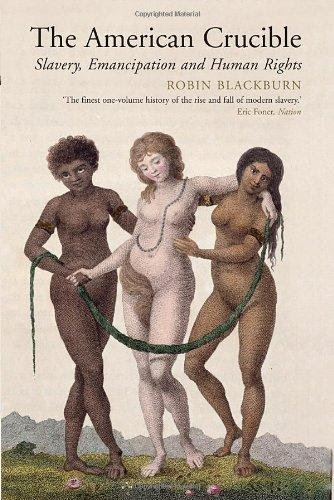

Marxist historian Robin Blackburn wrote, “The slavery of the New World permanently created, defined and embodied a violent subjugation of blacks by whites … antipathy and unconcern was transmuted into fear and domination.”

Industrialisation

Capitalism was already developing in Britain, but it’s no coincidence that it was the first country to undergo industrialisation.

As the revolutionary Karl Marx wrote, “Capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt.”

The transatlantic slave trade gave British capitalism an adrenaline shot and serious advantage over its competitors. Britain was in a prime position at one corner of the trade’s triangular route (see box, right).

The British ruling class lined its pockets with money exchanged for the lives of human beings.

A recent study by University College London found that one in five wealthy people had economically benefited from slavery at the height of the slave trade.

One slave owner, James Madison, described how he could make $257 dollars off a slave in a year and spend as little as $12 on keeping him alive.

Raw materials flooded into Britain from the plantations and cotton fields of the Caribbean and US.

Boomed

People were forced into factory towns to deal with the massive influx of produce. Manufacturing cities such as Manchester and ports such as Liverpool and Bristol boomed.

The growth of exports accounted for 87 percent of the growth of output in the period 1784-86 to 1805-07.

By 1795 there were over a hundred slave ships registered in the port of Liverpool alone.

That represented half of the entire capacity of the European slave trade at the time.

The slave trade and the plantation economy had become central to the growth of British capitalism. They provided the spark that ignited the Industrial Revolution.

While this was happening, African societies were being sacked.

Europeans needed to back up their scientific explanations for Africans’ inhumanity with “proof” of their backwardness.

Cities were razed, infrastructure destroyed, libraries torn apart, universities burned to the ground.

That was all part of an effort to destroy any evidence that Africans had built societies that rivalled European ones.

Apart from the millions of people taken from Africa, the slave trade had a devastating effect on those who were left. Some 25 to 30 million people were displaced in order to capture and transport 12 million.

At the time sub-Saharan Africa only had a population of 50 million people. The effect was felt for centuries afterwards.

European imperialists also created militaristic regimes.

People fought to sell their neighbours in the hope they would be spared.

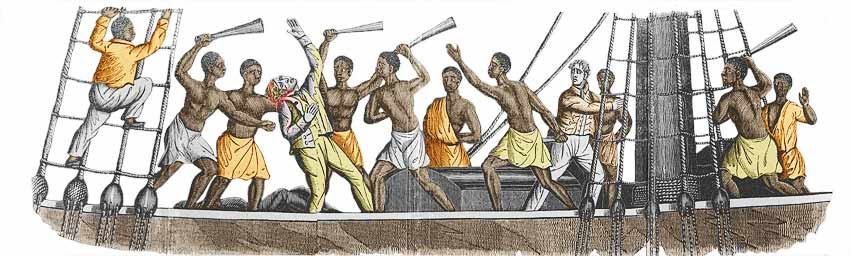

Despite this people would unite and fight back after being captured and transported.

Because they were forced into disgusting conditions, the only thing they had left was to fight. You were either ground down and died or stood up and fought.

‘I’d rather die than be a white mans slave’ – the story of the Amistad Rebellion

There were constant revolts and they were thoroughly documented because of the bureaucratic nature of the slave trade.

Slavers would document every time a slave died because they needed to be accounted for in the same way as any other property.

At the height of the slave trade there were revolts on a massive scale.

“Emancipation in the Americas was not achieved through the slow accumulation of concessions and customary rights,” argued Blackburn.

“It was marked by revolutionary ruptures, involving the action or reaction of the slaves themselves.”

Slavery was formally abolished after the US Civil War in 1865. But the ruling class still needed racism to fuel division, so their talk shifted from the “science” of race to the narrative of black people’s criminality.

As Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, explained, “Former slaves and their descendants were arrested for minor violations, slapped with heavy fines, and then imprisoned until they could pay their debts.

“The only means to pay off their debts was through labour on plantations and farms—known as convict leasing—or in prisons that had been converted into work farms.”

This narrative continues today with ideas around black people and “gang culture”.

Since capitalism’s birth, it has used racism to fuel divisions that help maintain its rule. But as capitalism developed, so did racism and who the ruling class’ main scapegoat was.

Scientific racism was largely discredited after the horrors of the Holocaust, when the Nazis murdered six million Jewish people and millions of others. Now racist discourse often focuses on people’s “culture” instead of “race”.

So, for instance, Muslims are blamed for their failure to “integrate” or hold “British values”, but this is mixed with older forms of racism.

Racism was born out of capitalism and the transatlantic slave trade—and capitalism continues to rely on it today.

As the revolutionary Malcolm X wrote, “You can’t have capitalism without racism.”

He was right. Our task is to get rid of both.