What is at stake when we talk about the economics of North American slavery? Over the last 75+ years it has been whether capitalism superseded slavery or whether capitalism and slavery were co-constituted, capitalism to some extent relying on slavery. Part of that discussion has been theoretical and part hinges on whether the exploitation of African-descended Americans is an incidental or an essential part of the economies of English and British North America and the United States over the last four centuries.

To get some perspective, I’d like to look at a sliver of that history and sketch some of its legacies. The 1655 voyage of the slave ship Witte Paard and its aftermath could help bring into focus some of the issues in the ongoing debate over capitalism and slavery. Rather than a discussion of capitalism as an economic system, I’d like to suggest viewing the relationship between forms of capitalism and slavery in terms of economic white supremacy. That is, a sustained yet protean process of disinheriting, dispossessing, and decapitalizing African-descended people. This isn’t a shift in understanding so much as perspective. Where one sits facing a disciplinary, geographic, or chronological boundary tends to influence where one stands on the relationship of slavery to capitalism and the ramifications of those processes.

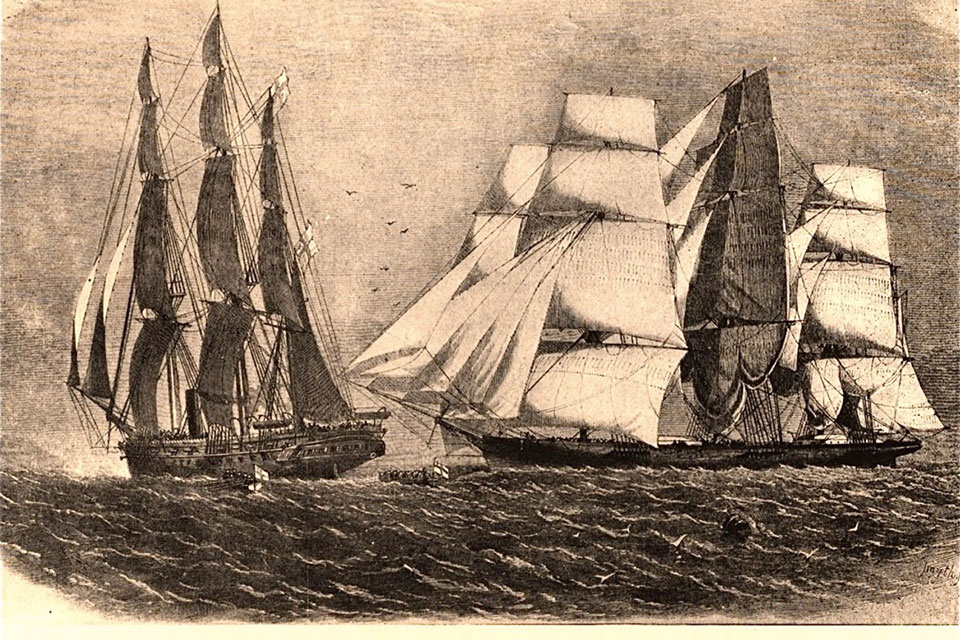

Sometime in late 1654 or early 1655, Antonio—a Kikongo or Kimbundu speaker—was captured and forcibly transported to the slaving port of Loango in present-day Republic of the Congo. He joined thousands incarcerated in squalid and cramped sites near the harbor. Antonio did not know it, but in 1654, two Dutch merchants had secured permission from the Dutch West India Company (GWC) to sail the Witte Paard (“White Horse”) from Texel to southwestern Africa and buy “Slaves” to sell in New Amsterdam. Records don’t reveal how Antonio, among 455 Angolan and Kongolese captives taken out into the harbor, responded to the sight of the Witte Paard anchored off Loango in the spring of 1655. Did they see it as a floating engine of capitalism? Or a vessel of degradation, suffering, loss, and death?

Before boarding, captors branded each with a red-hot iron, burning a customs stamp on the right breast or shoulder. As the ship sailed across the equator, Antonio and the other captives were probably unaware that Chesapeake tobacco planters had already applied for a share of the human cargo. One in seven died on the months-long passage that brought the survivors to Manhattan, residents complaining of the vessel’s stench filling the harbor.

Antonio languished in a New Amsterdam jail until Symon Overzee, a Maryland planter from a wealthy Rotterdam family, showed up to purchase him. It probably mattered less to Antonio whether Overzee’s economic strategy was capitalistic than the political and social framework that allowed him to claim the fruits of Antonio’s unpaid labor. Overzee took him back to Saint Mary’s City, and when Antonio refused to work as instructed Overzee tortured and murdered him. (You can visit the St. John’s site where it happened.) A Maryland court later acquitted Overzee, sanctioning the violent domination and destruction of Black bound workers. Back in New Amsterdam, other captives had remained incarcerated through the winter as Chesapeake planters showed up to buy them.

Edmund Scarburgh (or Scarborough) of Virginia’s Eastern Shore paid for 41 captives from the Witte Paard early in 1656, fulfilling an obligation he’d made in advance to buy a portion of the human cargo. Virginians like him defied the English Parliament’s 1651 Navigation Act requiring them to ship commodities on English vessels, preferring the reliability of Dutch ships and higher prices for their tobacco in Rotterdam via New Amsterdam than in England. “Colonel” Scarburgh was a thirty-eight-year-old planter and merchant whose diversified enterprise included a fleet of ships, a salt works, malt house, shoe factory, warehouse, an extensive herd of livestock, and tens of thousands of acres worked by scores of bound laborers, mainly English indentured servants.

He had used family wealth in England—his brother would be court physician to King Charles II—as startup capital in Virginia, paying for headrights (good for 50 acres each) and now enslaved people whom he identified as Angolans. His economic power supported his political ambitions, and he served as speaker of the Virginia assembly and surveyor general of the colony, along with other posts. He embodied the swaggering ambition of the English colonial project. And its racial bigotry. In 1651, Scarburgh had led a private militia to kill the king of the Pocomoke people and in the process massacred Accomacs in a bid to aggrandize land. The king survived. Virginia prosecuted him for the attack, but Scarburgh was too powerful to convict.

Scarburgh’s career seems at first blush like a prelude to what Sven Beckert terms “war capitalism” and an embryonic form of what Walter Johnson terms “slave racial capitalism,” while Antonio’s response to Overzee’s demands illustrates an early assertion of what Daina Ramey Berry calls “soul values.” Scarburgh’s career illustrates what S. D. Smith terms “gentry capitalism,” in a Virginia idiom. But it was also part of a move to support the growth of white wealth by stealing the work product of African-descended people.