By Susanna Rustin (The Guardian)

The UK continues the fiction that racial exploitation is in the past, says Matthew Smith. He hopes his London appointment will help change that

Matthew Smith did not plan to quit Jamaica. Until last year the historian, who previously headed the history and archaeology department of the University of the West Indies at Mona, near Kingston, had made a point of staying. “I wanted my career to be an example that you don’t have to leave,” he explains on a video call. But when the directorship of UCL’s Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership came up, he couldn’t resist. “I couldn’t think of a better job,” he says. “For me it was the perfect way to bridge research on the Caribbean with meaningful public engagement.”

Smith, 46, takes over the reins of the centre at an extraordinary time. Awareness of the UK’s role in slavery is arguably at an all-time high after the toppling of the statue of the Bristol slave trader Edward Colston in June.

UCL’s research centre has played a part: its database of compensation payments to British slave owners opened up this slice of history to the public. But Smith believes this knowledge is just the start of a long-overdue shift in historical awareness.

British Black Lives Matter activists are shining a strong light on British history and the choices made about how to remember it, and universities are among the institutions being forced to confront the ways in which they benefited from slavery and colonialism. Last year the University of Glasgow agreed to pay £20m in reparations via a partnership with the University of the West Indies. In Oxford, a commission is due to report on the future of Oriel College’s statue of Cecil Rhodes next year.

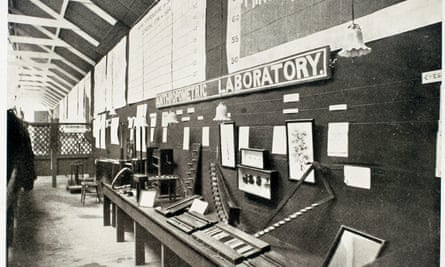

At UCL, efforts to confront the racist past have focused on the university’s links to eugenics, with a decision in June to rename facilities named after the eugenicists Francis Galton and Karl Pearson. Smith believes such steps are important and looks forward to joining the discussions about racism, past and present, at UCL. Currently he is working remotely from Williams College in Massachusetts, where he was staying when Covid-19 struck.

Having experienced racist treatment as a postgraduate in Florida, he is acutely conscious of the obstacles black and ethnic minority students face today. “The fiction told to descendants of the enslaved was that the horrible past of racial exploitation was over,” he says. “That fiction continues in 2020.” He says he has noticed a “bluntness” in British racism: “it doesn’t pretend to be diplomatic, it’s very clear and sharp”.

In addition to financial reparations and forms of recompense such as positive action schemes, Smith believes history itself can serve a reparative purpose. UCL’s database containing details of some 61,000 individuals connected to the slavery business, about a quarter of whom were women, opened many people’s eyes to the fact that when slavery was abolished, British slave-owners were compensated while slaves were not. Now Smith and his colleagues plan to switch their focus to the lives of those who were enslaved.

“Looking at the decline of sugar, and the establishment of free villages, and joining all that up with the corpus of remarkable historical scholarship on post-slavery Caribbean societies can give us a much firmer understanding of the impact of slavery on the enslaved and their descendants, how it led to emigration and so on.”

Smith’s enthusiasm for his subject comes across in everything he says. His mother, who worked as a freelance typesetter after leaving school at 15, encouraged him to read magazines she worked on, including the Jamaica Journal. His father was a self-employed salesman who took pride in his studious son. Smith says he has never forgotten the atmosphere of the lessons in which he and his classmates were first taught about their ancestors’ struggle for freedom. “The history of slavery was fundamental, I learned it very early on, I may not have understood every aspect but I was very much aware of it as an aspect of our national story,” he says.

In the UK, by contrast, slavery has traditionally been about as far from a main component of the national story as it is possible to be. Where it is discussed, the dominant narrative has usually been about the fight for abolition led by William Wilberforce.

“It was an active campaign that was very much connected to black consciousness,” Smith says of the work done by the first generation of post-independence Caribbean historians, who are among his heroes (and one of whom, Eric Williams, became Trinidad’s first prime minister). But while he was drawn to follow in their footsteps, finding new ways to interpret the hierarchies of race, colour, class, language and nationality that shaped plantation societies and persist to the present day, he has long been conscious of swimming against a tide of those who would rather forget.

“It might seem like a strange thing to say but because they learned it through school, and because of its darkness, there is a resistance to studying slavery among Jamaican students in the 21st century. There is this sense that it is more of a lodestone than a launching pad for success.”

Researching the lives of slaves is also difficult. There are registries of slaves, but no Caribbean equivalent to the first-person account of the American captive Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave. Smith traced five families over five generations for one of his books, and explains that while the physical evidence of slavery is everywhere in Jamaica – the university campus where he worked for 18 years is based on two former plantations – research about people is made “very complicated by the assigning of new names, the division of families … you hit pitfalls and roadblocks in the early 19th century”.

The official investigation into the Windrush scandal said that “poor understanding of Britain’s colonial history” was one reason why British people who had arrived in the UK from the Caribbean as children were appallingly mistreated.

Smith plans to work with museums and other partners to increase awareness. But it is not only in the UK that he thinks Caribbean voices, and those from other former colonies, need to be raised. In the US, too, he has been troubled by the lack of interest. And so it is as a kind of ambassador that he comes to London, with his wife, a social scientist, with plans for digital classrooms bringing together British students with students in Barbados, Trinidad or Jamaica.

“Looking at what happened to freed people and their descendants means having an active dialogue with the Caribbean, and this is what excites me.”