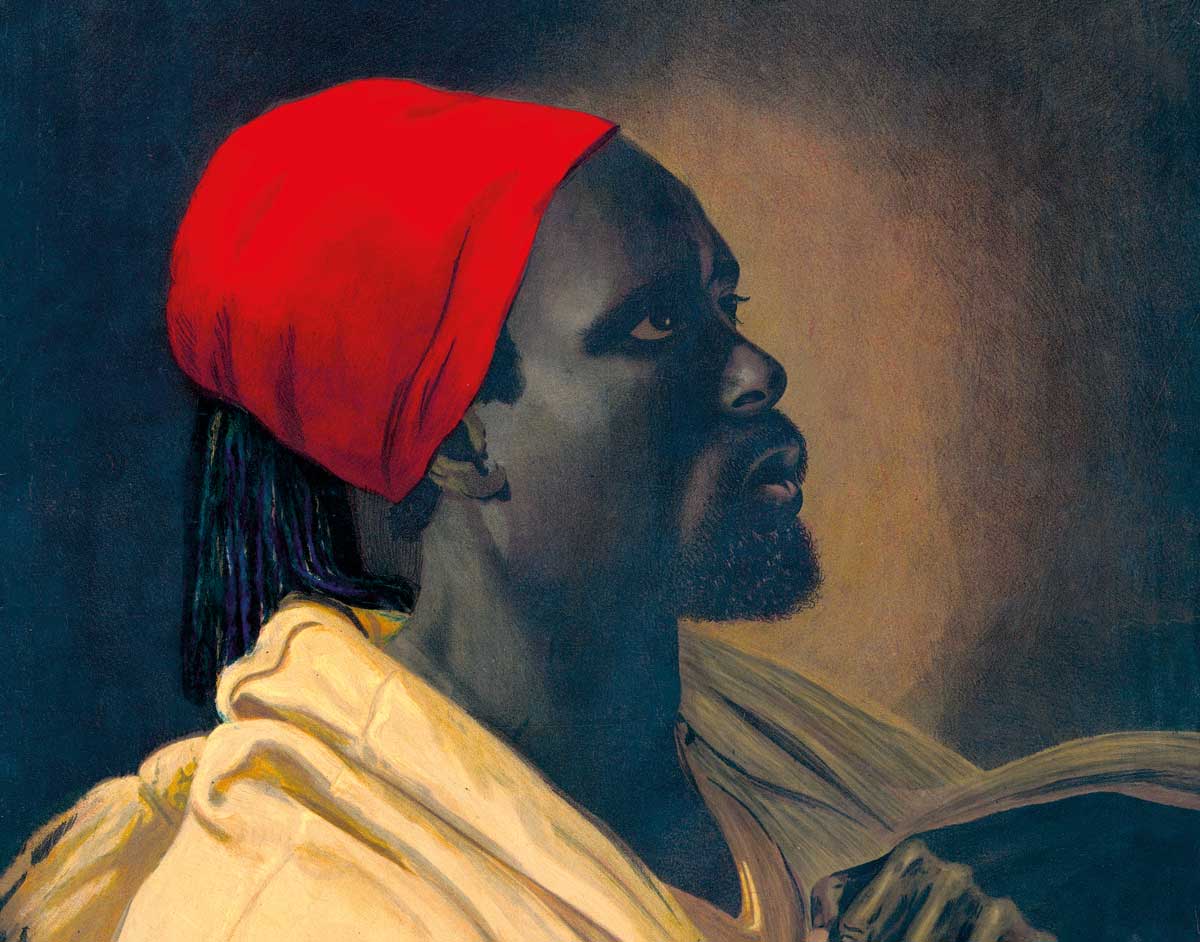

The hero of the Haitian Revolution’s lonely death in a French prison cell was not an unfortunate tragedy but a cruel story of deliberate destruction.

On the morning of 7 April 1803, Toussaint Louverture, leader of the slave insurrection in French Saint-Domingue that led to the Haitian Revolution, was found dead by a guard in the prison in France where he had been held captive for nearly eight months. The guard, Citizen Amiot, had written to the French Minister of the Marine in January 1803 describing Louverture’s condition as grave: he was suffering from constant fevers, severe stomach aches, loss of appetite, vomiting and inflammation of his entire body. Despite the fact that Amiot’s predecessor, Commander Baille, had reported similar problems to French officials the previous autumn, no doctor had ever visited Louverture while he was alive in Fort de Joux.

It was only after Amiot found Louverture’s lifeless body – his head resting upon the woodless chimney in his cell, as though he were in gentle slumber rather than in rigor mortis – that a surgeon, Gresset, and his medical apprentice were brought in to assess him. After ‘scrupulous’ examination Gresset observed that Louverture was ‘without a pulse, not breathing, heart devoid of movement, skin cold, eyes still, [with] stiff arms’. He concluded that the prisoner was ‘truly dead’, a strange turn of phrase for a case that must have been obvious. The official autopsy described Louverture’s lips as having been tinged with blood.

The seeming incredulity in these words was at least partially a result of the fact that Louverture had been accused of faking his physical ailments in the months leading up to his demise. The previous October, Louverture asked Baille to tell the government that his cell, which was often freezing, was too cold. Baille acknowledged Louverture’s claims that the temperature was causing him to suffer almost constant coughing, along with rheumatic pain throughout his body. But Baille told Minister Denis Decrès that more firewood would not be necessary since the captive was likely faking his symptoms; yet more proof of what he called ‘that destroyer of humankind’s aggregated monstrosity’.

In September 1802, Louverture, with the help of his fellow prisoner, his servant Mars Plaisir, gave a written memoir to the man Napoleon had sent to interrogate him, General Marie-François Auguste de Cafarelli. In the memoir, Louverture defended his conduct as a French general and complained directly about the treatment he was receiving despite his title and rank. Louverture also made it clear that he believed that all that had led up to and befallen him since his arrest in June was due to the colour of his skin. ‘Without a doubt I owe this treatment to my colour’, he wrote. ‘But my colour, my colour, has it ever prevented me from serving my Country with diligence and devotion?’:

Arbitrarily arrested without anyone explaining or telling me why, all of my assets seized, my entire family ravished, my papers confiscated and kept from me, shipped out and sent over here, nude like an earthworm, with the most atrocious of calumnies having been spread about me, is that not to cut a person’s legs and then order him to walk? Is it not to bury a man alive?

His previous guard, Baille, confirmed in a letter to Decrès that he was denying medical care to Louverture because he was black: ‘The composition of negroes being nothing at all resembling that of Europeans, I am ill-inclined to provide him with a doctor or a surgeon, which would be useless in his case.’ The meticulous records kept by the French government suggest that Amiot was dangerously obtuse, at best, or criminally disingenuous, at worst. When questioned about how Louverture’s condition became fatal under his surveillance, Amiot’s only defence was to state that Louverture ‘never asked for any doctors’.