The Amistad Rebellion tells the story of a group of slaves who rose up. Ken Olende looks at a revolt that caught the imagination of poor people everywhere—and showed slaves could win

In July 1839 the Amistad set sail from Havana in Cuba. It was carrying 49 men and four young children, slaves recently bought in West Africa. After four days at sea the slaves rose up and took over the ship. American historian Marcus Rediker’s new book on the uprising, The Amistad Rebellion, reads like an adventure story.

The Africans, unable to sail the ship, were captured by the US and put on trial. Had they justly liberated themselves, or stolen their masters’ property? The court case and unprecedented popular interest at the time mean there are detailed records. Contemporary accounts of slaves and their African roots are highly unusual.

Rediker talked about their lives in West Africa. He explained, “Moru was a Gbandi man, born in Sanka. His life took a hard turn when, as a child, both of his parents died… he became a warrior, and eventually a slave; perhaps he was captured in battle. His master, Margona, a member of what would become the ruling house of Barri Chiefdom.”

Even today many people will be surprised to hear that almost all the slaves had lived in towns or cities. They suffered the horrors of the middle passage across the Atlantic to the Americas. The Atlantic slave trade had been officially banned at this time, so slave traders were smugglers.

Vessels transporting slaves were smaller and faster, in order to outrun patrol ships. After centuries of human trafficking those that made the Atlantic crossing were well designed to resist any revolt by slaves. But the much smaller schooner Amistad, which took the slaves on from Cuba, did not have such defences.

Many slaves had to sleep on deck and there was no separate area for the crew. The slavers treated the Africans terribly. They gave them little food and only half of a teacup of water twice a day despite many being on deck in the midday sun.

The Amistad’s cook tried to terrify the Africans into submission by indicating they would be killed and eaten. Rediker explained, “In their African homelands people had long believed that the strange white men who showed up on the coast in ‘floating houses’ were cannibals.

Those forced aboard slave ships often thought that the casks of beef they saw held the flesh of previous captives and the puncheons of red wine held their blood.” The captives discussed what to do collectively. One asked, “Who is for war?” and the vast majority said they were. A rice farmer known as Cinque came to lead the revolt.

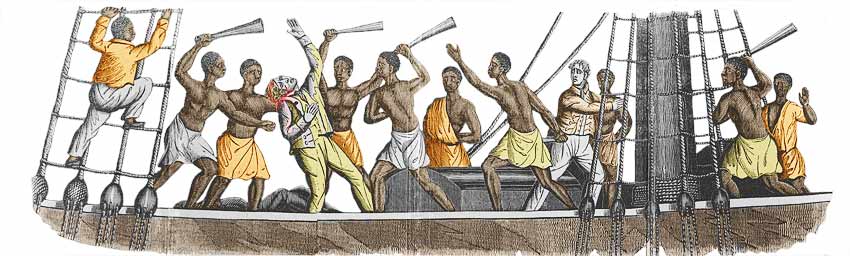

They killed the cook and stormed the deck. In a short, brutal battle they won control of the ship (see book extract below).

Cheated

The Africans indicated to the surviving crew that they were to sail them back to Africa—by sailing east by the sun. The crew cheated them however, sailing east as slowly as possible by day and back west as fast as possible at night.

After some time and very short of water they fetched up off the coast of Connecticut in the northern US. As soon as they came ashore the slavers told their side of the story and demanded the Africans be imprisoned for murder, theft and piracy.

The US was divided between slave states and those that where black people were legally free. Connecticut was a free state. But the law was very vague on whether a slave in one state who moved to a state where slavery was illegal remained a slave.

The Africans, still very uncertain about exactly what was going on, were thrust in New Haven prison to await trial. Their arrival created an immediate storm. People thronged to the jail to meet them. A play was written and popular prints were circulated.

These were for the poor, who admired the slaves’ revolutionary zeal. Whatever the legal system said, in the popular imagination their rebellion was rightly seen as an act of liberation. The truth could only emerge once someone could talk to the Africans. They enthusiastically set about learning English, but it was a slow process.

The children taught the linguist Josiah Gibbs to count from one to ten in their language, Mende. He travelled to New York and walked around the docks loudly counting until, as he had hoped, two African sailors asked how he knew Mende.

Charles Pratt and James Covey were Mende sailors on a British warship, so they both also spoke English. Gibbs borrowed them as translators. Suddenly the situation changed. Up to now, only the slavers’ story had been heard. Now it was possible for the Africans to tell their side.

Cinque said he would rather die than be enslaved again. It reminded many Americans of the cry from their own revolution less than 60 years earlier, “Give me Liberty or give me death”. Anti-slavery activists, or abolitionists, flocked to help the Amistad Africans. But as Rediker said, they “sought to turn those who had engaged in communal armed struggle into peaceable, disciplined Christians”.

Their ideal images were passive ones, such as Josiah Wedgewood’s famous “Am I Not a Man And a Brother?” The popular prints of armed rebellion made them uncomfortable. To modern ears the terms of the trial sound absurd.

The Africans’ lawyer John Quincy Adams pointed out that the slaves were both accused of being passive cargo and active “pirates” who stole themselves from their owners. But legally it was considered that they could be returned if they had been legal property in Cuba, not newly stolen from Africa.

So the case of the slave cabin boy Antonio did not come to court. He grew up in Cuba, so he was simply to be returned. Antonio didn’t see the situation in this light and fled to Canada. To the outrage of pro-slavery newspapers the judge found for the Africans. The slavers immediately appealed—and lost. The Africans were freed, but the court did not offer to return them home. They toured to raise money and looked to missionary groups to help them get home.

Eventually they sailed for Sierra Leone with a missionary group. The white missionaries and the freed Africans respected each other, but had very different ideas about what would happen when they got to Africa. The Americans were pleased that the Africans had been civilised and would take the gospel and US values back with them. But the Africans did not want to abandon their own cultures. The missionaries were shocked how quickly they abandoned Western dress back in Africa.

They were also shocked to find that this was a class society, whose rulers cared little about poor Africans being traded as slaves. A missionary accompanied Burna, one of the rebels, when he finally returned to his mother’s home after a mysterious three-year absence. He saw his mother break down in tears of joy and wrote, “I had never before seen such an expression of nature’s own feelings, unrestrained by art or refinement.”

Rediker also tells the story of Madison Washington, a former slave who had escaped to Canada, but determined to go back south to find his wife. He was betrayed and sold back into slavery.

At the end of 1841 he was transported along the coast of the southern states in a ship, the Creole. Inspired by the Amistad story he led a revolt which took control of the ship—killing the slave agent and wounding the captain. He sailed to the Bahamas, then under British control. The US government demanded the return of the slaves as US property, but they were denied.

Britain’s rotten role

British ships dominated the Atlantic slave trade in the 18th century. The trade funded much of early industrial capitalism. But after a series of slave revolts in the Caribbean and mass campaigning in Britain the slave trade was banned in the British Empire in 1807.

Britain’s rulers were determined to ensure that if they couldn’t make profits from the trade no one else would. The British navy patrolled the seas to block slavers. Slavery itself wasn’t banned in the British Empire until 1833 when further revolts and campaigning made it untenable.

The British government showed how much it really cared about slaves when it compensated slave owners for loss of property, but not the slaves.

‘He believed, wrongly, that the Africans were all great cowards’

“More Africans escaped their chains and joined the fray, wielding the fearsome machetes that had been found by the little girls, who had free range of the vessel. Seeing that the situation went far beyond exhortation, Ruiz called on Montes to kill some of the rebels in order to frighten the rest and to restore order. He believed, wrongly that the Africans were all ‘great cowards’.

At first the crew and passengers were able to drive the rebels from amidships beyond the foremast, and at this point Captain Ferrer, who desperately hoped this was a rebellion of the belly commanded Antonio to fetch some sea biscuit and throw it among the rebels in the hope of distracting them… Antonio did as his master commanded, but the insurgents, he explained, ‘would not touch it’… Several of the Africans were reluctant to attack the captain until Cinque exhorted them to do so.

A small group formed a ‘phalanx’ to surround him, machetes in hand. As the battle raged, Captain Ferrer killed a man named Duevi and mortally wounded a second, unnamed rebel which infuriated the other Africans and made them fight harder…Cinque and the other leaders of the rebellion now surrounded Captain Ferrer in a fury of flashing blades. Faquorna apparently struck the first two blows. Cinque struck the last one.”